Script for Graphic Narration

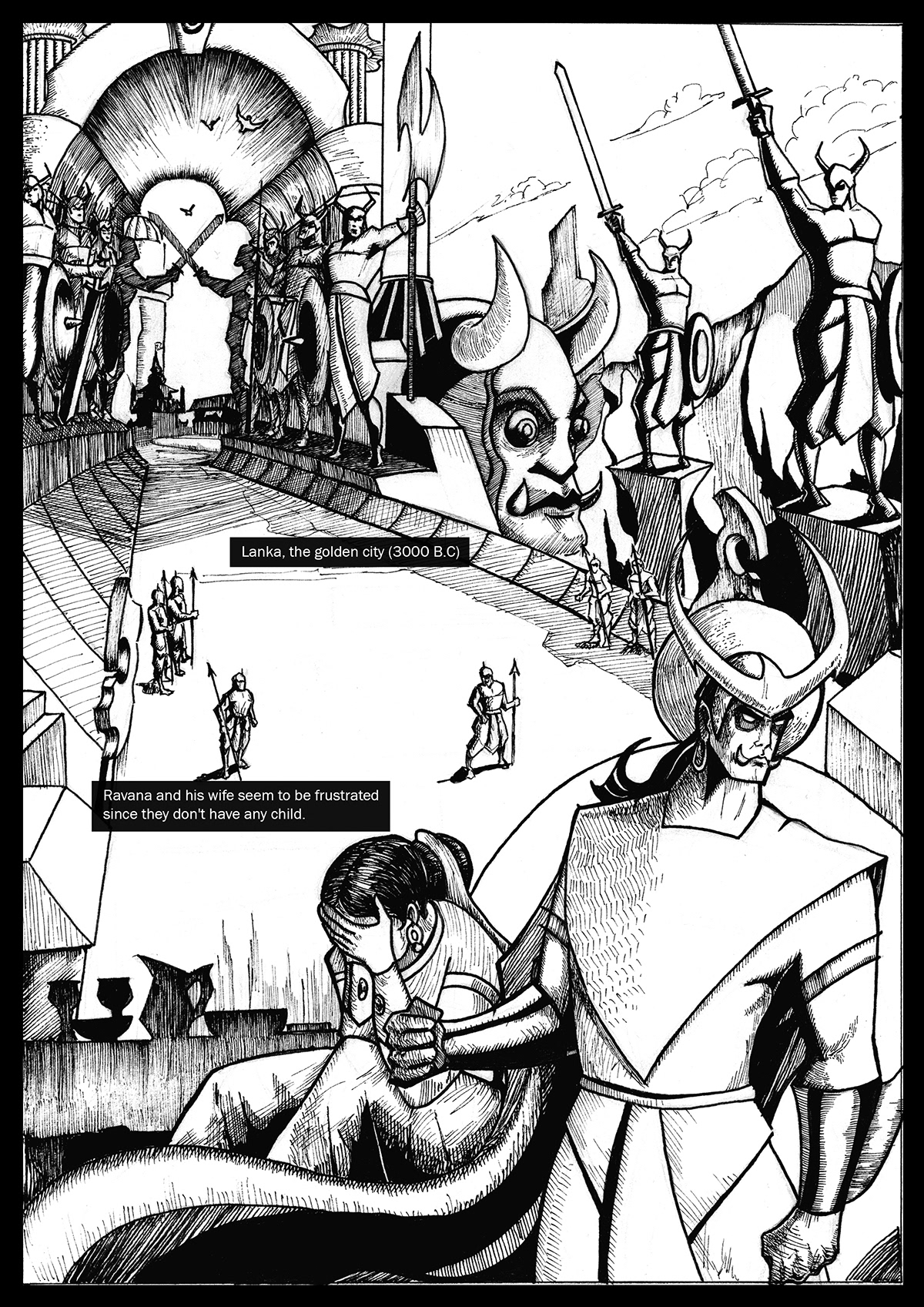

Ravana and his wife seem to be frustrated since they don't have any child.

So he decides to do intense tapasya to please Shiva.

Finally, Shiva appears in front of Ravana and grants him a boon.

Ravana is given a mango but was also warned by Shiva that the fruit pulp was to be given to

Mandodari and he has to only taste the seed.

Upon returning the palace...

Ravana gets attracted towards the mango.

So, he consumes the fruit pulp and gives the seed to Mandodari.

This resulted making Ravana pregnant. Later he suffered from a lot of pain.

Also, each day that passed was equal to a month.

After 9 days, he sneezed and a girl child took birth from his nostril.

Ravana was told by an astrologer that he will be punished since he disobeyed Lord Shiva.

So, the astrologer advised him to feed and dress the child and also leave her to a place where she could be found by a couple.

So he put her in the box and leaves her in King Janaka's field.

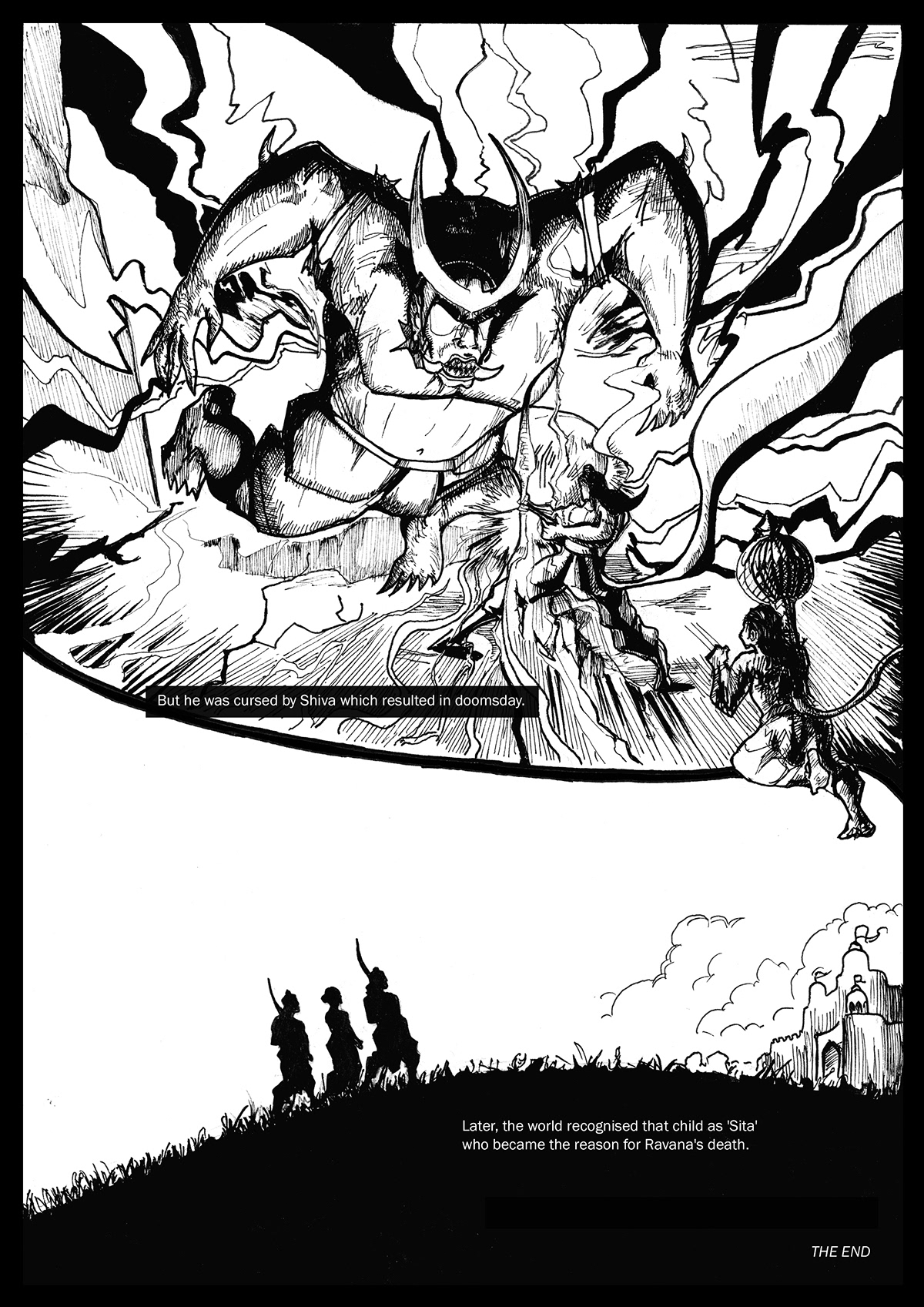

But he was cursed by Shiva which resulted in doomsday.

Later, the world recognised that child as 'Sita' who became the reason for Ravana's death.

So he decides to do intense tapasya to please Shiva.

Finally, Shiva appears in front of Ravana and grants him a boon.

Ravana is given a mango but was also warned by Shiva that the fruit pulp was to be given to

Mandodari and he has to only taste the seed.

Upon returning the palace...

Ravana gets attracted towards the mango.

So, he consumes the fruit pulp and gives the seed to Mandodari.

This resulted making Ravana pregnant. Later he suffered from a lot of pain.

Also, each day that passed was equal to a month.

After 9 days, he sneezed and a girl child took birth from his nostril.

Ravana was told by an astrologer that he will be punished since he disobeyed Lord Shiva.

So, the astrologer advised him to feed and dress the child and also leave her to a place where she could be found by a couple.

So he put her in the box and leaves her in King Janaka's field.

But he was cursed by Shiva which resulted in doomsday.

Later, the world recognised that child as 'Sita' who became the reason for Ravana's death.

Note on Ramayana-The Epic

-Suryansh Srivastava

From generations India has grown up with what we can say is Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayana version which was the adaptation of the ancient Hindu religious epic of the same name. Throughout Indian history, many different telling and performance have been produced by various authors, artist and performers perhaps people develop reluctance for the ending of this epic and it’s always welcomed with great enthusiasm in India and beyond.

The great Hindu epic, Ramayana teaches Indians the idealistic way and manners of living life, for a peaceful and eternal existence. It contains the magnanimous knowledge of philosophy, customs and religions, polity, social life, religion, ethics, code of conduct, etc. and one can see its various tellings in India and South-East Asia where it upholds decisive role and values in the lives of the people and has greatly influenced art and culture in the Indian subcontinent and South East Asia from the past two millennia, with versions of the story also appearing in the Buddhist canon from a very early date. Ramayana, (Sanskrit: “Rama’s Journey”) shorter of the two great epic poems of India, the other being the Mahabharata (“Great Epic of the Bharata Dynasty”). The Ramayana was composed in Sanskrit, probably not before 300 BCE, by the poet Valmiki and in its present form consists of some 24,000 couplets divided into seven books. Though Valmiki’s Ramayana was the earliest, prestigious and extensive early literary treatment of the life of Rama and often considered as original or Ur text, it’s not that this version of Ramayana that travelled and carried forward from one language to another.

Ramayana can be stated as symbol as the essay demonstrates the fact that how the story of Rama has undergone numerous changes and variation while being translated and transmitted across different languages, societies, geographical regions, religions and historical periods.

Ramayana is much more the allegorical epic from which people create their own meaning and significance. It got its different meaning in the context where this epic has been performed or read. Ramayana’s significance goes beyond the textual texture and its rendition occurred from the heart of the various culture. Regardless of the different forms which are shaped by religious incorporation, linguistic fealty and social situation, ‘the story’ remains inextricable. The story of Prince Rama's quest to rescue his beloved wife Sita from the clutches of Ravana with the help of an army of monkeys.

The text is the genre with a variety of instances and when focused specifically on characters holding symbolic meaning, it leads to different interpretations of different people and culture. When one accounts for the character, like the story of Ahalya, the virtuous fallen women who commit adultery having the same plot both in Valmiki’s Ramayana in Sanskrit and Kampan’s Iramavatram (The incarnation of Rama) in Tamil though got different texture and colours of the same telling and can have a common interpretation that the un-plow-able (A-hal-ya) and infertile land around Gautma’s hermitage might have become barren due to excessive rain and over use. This excess water from Indra’s rain might have chunked and brings up chemicals up to the soil making it infertile. So this perhaps can explains the story of Ahalya as she became invisible and dwell in that place because of the association with the Indra (invisible in Valmiki’s and stone in Kampan’s). Only later when Rama during his exile and set his foot on Ahalya (worked on the infertile land), she would restored her life completely. In Valmiki’s translation of Ahalya plot, Kampan adheres with the story plot, sequence, and structural relationship with the characters and tries to preserve basic textual features.

(An extract from THE AHALYA EPISODE: KAMPAN) (Ramanujan, 1991)

‘Gautama's mind had changed

and cooled. He changed

the marks on Indra to a thousand eyes

and the gods went back to their worlds,

while she lay there, a thing of stone. [558]

That was the way it was.

From now on, no more misery,

only release, for all things

in this world.

O cloud-dark lord

who battled with that ogress.

black as soot, I saw there

the virtue of your hands

and here the virtue of your feet.' [559]"

When this epic passes from textual to oral tradition like that in Kerala’s Puppet play (Olapavakuthu) which focuses on diversities among the Ramayana tradition inspired by moral ambiguities (Blackburn, 1991), the textual conversation of Ramayana that held dialogue on three levels, each of which has listeners and audience internal to its performance. It includes certain anti heroic interpretation of certain events in Rama’s story. There puppet plays recitation are verbal ritual (puja) intended to gain benefits for the sponsors. In central Kerala, the oral telling is the part of the annual festival to the goddess Bhagvati. It holds the textual verses of Kampan’s epic poem, the Iramavataram and it’s more a commentary rather than narrative form of the Ramayana. Now here conventional audience are discouraged as the language of the verses is a medieval Tamil which is scarily understood by local Malayalam speakers. Distance somehow created by the language as well as the screen dropped between the performer and the audience. The dominance of the commentary thus make the show much like static staged and frieze rather than a film. Outside, it’s a ritual act but inside it’s an ongoing inner conversation. In the tellings of the Rama story, talking is no less important than event of the tales. Apart from the villagers and patrons present their as an audience there is the another external audience for puppet play that is goddess Bhagwati as the origin legend of this puppet show tradition begins that o server she was the Bramha’s treasury guard and was send Lanka’s treasury as her proud grew. When Hanuman slapped her with his tail upon blocking his path, she was sent to Shiva’s heaven. There she complaints that she could not see Ravana’s end. Then Shiva gave her boon that she will be born as Bhagwati and he will be born as Kampan and each year she will watch the Kampan’s poem in her temple. So, Bhagwati is the public audience and this puppet show was to please her.

Above is evidence, that how the Ramayana as epic has a capacity to create a story within a story in different context. So, adapting the Kampan tellings to shadow puppet play, their tradition has developed several layers of communication and communication is only possible when that ‘text’ can be translated and metamorphose into different plots.

While considering non-traditional perspective, like EV Ramasami’s reading of the Ramayana by Pula Richman which accounts the fact that Ramayana had been proved as an effective means of conveying political views and infusing religious teachings (Richman,1991). E.V.Ramasami criticizes the dominance of north Indian Brahmanical Hinduism where he disdains the Rama’s part and instead identifies Ravana as a monarch of the ancient Dravidians. Similar to some context of Ramanujan’s Jain tellings where Ravana is one of the sixty-three leaders of them and their story opens with the pedigree and greatness of Ravana instead of Rama’s. The Dalits, a group of militant Maharashtra have considered Ravana as one of their hero. Many Dravidian and local tribes of southern and central Asia have caste tradition that connect them to Ravana and Lanka.

Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translations is an essay by Indologist A.K. Ramanujan in which he surveys a wide range of Ramayana stories that are still surviving in Asia. It talks about the history of the Ramayana and its spread across India and South East Asia over a period of 2500 years or more.

We can see that these all variations of the epic are ‘context-sensitive’ as they do have a common grammar in different geography, religious affirmations and culture. And in some sense cultures are comprehensible and universal. These telling share common context but differ in their structure and structure is created by the practice which is reinforced by it. In analysing the textual diversity, Ramanujan’s essay shares the plurality of Ramayana through five different essays in different parts of India and Thailand. By looking at five different Ramayanas: Valmiki’s Sanskrit poem, Kampan’s Iramavatram, a Tamil literary that accounts South Indian material, Jain tellings, which counterstrike the image of Ravana by producing their own text, a Kannada folktale that reflects the preoccupations with sexuality and child-bearing; and the Ramakien, The Thai version, Hanuman is not considered as celibate devotee with monkey face but a ladies’ man who figures in many of the love episodes, he challenged the way to find the articulating relationship among these.

Ramanujan opened up with the first and foremost argument that can we consider the earliest version of the epic’s narration as an original tale or Ur text which was already there in Asian subcontinents. With a story of Rama’s visit on earth as avatars, the story’s end brings to Hanuman that there is no one Rama, there are many Ramas and there is no one Ramayanas, there are many Ramayanas and every Ramayana has its own Rama. With the list of languages, it travelled far to the Annamese, Kashmiri, Bengali, Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Tibetan, etc. and they host their own version of Rama’s story. There can be much increment in the retellings of this epic if one also accounts the plays, dance-drama, sculptures and reliefs in both classical and folk traditions. This epic went through the translations with a relation of iconic, or with locale text i.e. indexical and producing counter text symbolically.

Due to diversity and spread of different tradition, the consideration and privilege given to one text of narration as an original and other as mere variations of that do not affect in a way in which the ideas and different languages and culture work. The third point he makes in the context of narration through the example of Jain tellings of the Ramayana. They question about the Ravana evil character who is Brahmanical imagination. They considered him as a noble who is fated by his karma to fall for Sita and bring himself his death.

Some retellings may be influenced by individual religious communities and specific configurations of the social relations. The question of folk traditions of the Ramayana is more difficult to address because we move into a different realm, from the written text to orality. Using a Kannada folk tale who focusses on Sita instead of Rama, it's about the birth of Sita from the nostril of Ravana. This section is devoted to banishment, pregnancy and reunion of Sita. It gives a whole new suggestion of father bearing the birth of child.

Further in the Southeast Asian text, like in Ramakien, Rama is seen as a human hero rather than a god and they neither consider this epic as a religious work. Thai history was full of war and survival that’s makes their people enjoy the abduction of Sita, details of war, the techniques and the fabulous weapons. Ravana was also admired here as seen as resourcefulness and learning, even Sita abduction is viewed with sympathy.

Thus, the Ramayanas tellings are not constrained to a context, it got its versions in different context that comes under a common shadow holding the same name making it context sensitive rather than context-free which was tried by the aired version of the Ramanand Sagar’s (1987) that in some extent created the coherency in Indian audience which was based on Valmiki’s and Tulsi Ramayana. Homogenization in this, in some way, would cause the cultural loss and other tellings might get depreciated.

Ramanujan concluded his essay with a tale of the mental and social elevation of a village dolt after he actually listened to a recitation of the “Ramayana”. So, Ramanujan in his essay is suggesting that there is no apex Ramayana that can be held sacrosanct. It’s the epic that appeals different people in different ways.

Thus, tellings, transpose and transcriptions of an epic vary upon the culture, people and their historical influences and it takes completely a new form as per the context and creates a story from a story.

References:

2) Richman, Paula, editor. Many Ramayanas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991.

Overview