Extreme wealth inequality in Mexico City's Santa Fe neighborhood

Mexico City is a bustling, enormous, modern city, one of the largest in the world. Triple-decker highways and gigantic tunnels bore through the mountainous terrain. Towering skyscrapers, enormous cathedrals and one of the world’s largest squares sit impressively atop a gigantic drained lake. Everywhere there are signs of the Aztec empire which came before - in the street names, the festivals, the food, and the eyes and skin of the population. It is truly one of the most fascinating cities I’ve ever been to.

Mexico is also one of the most unequal countries in the world. At one point, the world’s wealthiest man was a Mexican. The wealthiest 1% of the population earns 21% of the nation’s total income, a percentage higher than any other country in the world (http://www.socialprotectionet.org/sites/default/files/inequality_oxfam.pdf). Significantly, much of that wealth is concentrated in just a few multimillionaires. By some measures, the top 4 richest men in Mexico concentrate 9% of the wealth, a staggering amount in a country this large.

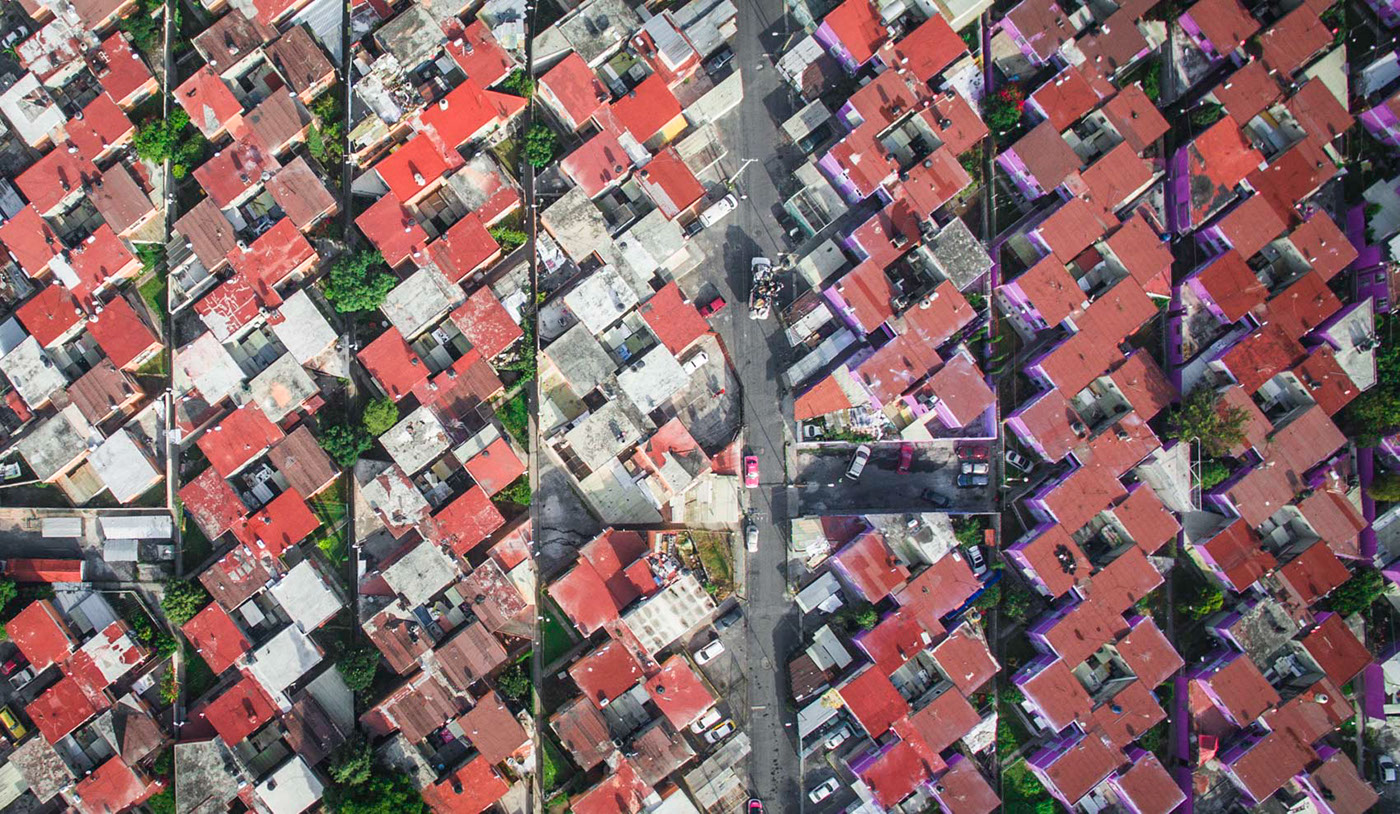

In Mexico City, that wealth is juxtaposed with enormous, sprawling lower income housing areas. Sometimes referred to as “slums”, areas like Ciudad Nezahualcoyotl feel more like gigantic worker’s colonies. As far as the eye can see, 2 and 3-story poured concrete houses stretch into the distance in a flat plain next to the airport. Somewhere between 1 and 2 million people live here, in a vast zone which also comprises neighboring lower income communities like Chimalhuacan and Ixtapalapa.

Neva is the biggest "slum" area I've ever been to. Well over a million people live here in a gigantic concrete grid.

Gone is the friendly, welcoming dynamic which exists in slum areas of Africa and India. In Neza, children peer cautiously out of windows, instead of swarming around my camera asking for a photo. Men and women eyed my camera distrustfully, suspiciously. More than once I was told to go away, not to film, even while working with a local fixer.

The conditions of organized crime are so bad, parents are forced to wear laminated ID cards around their neck when picking their children up from school. The reason? Kidnapping. As one woman told me, “they take photos of the children and share it on social media. That’s how they know which ones to take. This is why we don’t like cameras.”

Although the overall tone is grim, life goes on like it does anywhere. Mexicans take great pride in their food, their meat, and their spices, and roadside food stalls provide you with an opportunity to meet, chat, and understand one another in a safe place. Great metal artworks of a coyote and an Aztec soldier tower above Neza in a strange Socialist/Animistic amalgamation that I couldn’t imagine happening in any other city. Heavily armed police, some masked and riding on the back of pickup trucks with mounted machine guns, patrol everywhere. The Mexicans I talked to remarked that the more police they saw, the less safe they felt.

Every day in lower income areas of Mexico City like Ixtapalapa, there will be a market. From the air, they are easy to spot: A red streak gleaming like a beacon amongst a sea of drab concrete houses. Everything is traded at these markets - clothes, food, electronics, and everything in between. It's an example of the beautiful and colorful idiosyncrasies that make up contemporary Mexican life.

In direct contrast to many other lower income areas, I sensed little appetite to criticize the government, or the upper class. The lower-income citizens I talked to were resigned, perhaps too busy, perhaps too removed, to contemplate income inequality. Or perhaps it was something else entirely. Maybe they were wary of opening up to a foreigner, especially one with an American accent. Perhaps they were too scared to criticize, even fearful. Whether it was my presence or the general feeling of the community, I’ll never know. Maybe Mexicans in lower-income areas have simply adapted to the trauma of the drug violence, the corruption, the grinding banality of poverty, and learned to suppress their true emotions. Maybe the unwillingness to engage with a temporary visitor, a non-Spanish speaker, a white American, was purely a tactical question of time and understanding. I left Neza feeling like I knew less about the people, the community, than I did in almost any other city. No one offered me their email address, or their phone number. No one invited me back the next time I visited.

A special thanks goes out to the support structure I had in Mexico City, a very intimidating place to travel, speak, and drive. I could not have done this project without the support of the Thomson Reuters Foundation (specifically Anna Yukhananov), my driver Octavio, and of course my incredibly generous friends Alejandra and Daniela Esponda. A special thanks goes to Oscar Ruiz, a helicopter pilot who also happens to be a photographer specializing in photos of inequality. He created an incredible series that you can find here: (http://www.amusingplanet.com/2014/08/oscar-ruizs-aerial-photos-of-mexicos.html) which I used in part as reference for my own photos (see if you can spot the similarities!). He is also a very generous guy and spent part of his valuable time talking to me one day about his work.

The size and scale of the housing arrangements in Mexico City is just as fascinating as the wealth inequality between the two sides.

A gated housing estate in the Ixtapalapa neighborhood sits next to a classic concrete low-income area.

From above, the city grid of Ciudad Nezahualcoyotl (Neza) looks like an endless series of Christian crosses. Mexicans have a deep and almost mystical relationship with the Catholic church. Every street I went to had a shrine of the Virgin Mary, fresh flowers, and burning candles. Religious iconography is common everywhere, from bumper stickers, to tattoos, to street names.

Socialist-style housing estates are common in Mexico City, presenting amazing views from the air. They are usually colorful, enormous, and endlessly replicating the same pattern for the millions of people who live within them.

In Santa Fe, land is at such a premium that developers have begun to carve out housing estates from the surrounding slum areas.

A housing estate sits carved our of the barrio in Santa Fe, as the skyscrapers behind represent the great wealth of the area.

This highway clearly divides the barrio section from the mansions and estates of Santa Fe, Mexico City.

Another view of the highway which divides Santa Fe between rich and poor.

In the area of La Malinche, the barrio meets the wealthy areas next door. This private school offers tennis, basketball, and a well maintained pool, whereas next door the barrio only has a misshapen soccer pitch.

The area of La Malinche is beautiful, impoverished, and right next to much wealthier areas.

Barrios extend from the bottom to the top of a ravine in Mexico City's Santa Fe neighborhood. Above, the skyscrapers represent the wealth of the elite who live just on the opposite side of this highway bridge.