The United States Postal Service:

A Physical Representation of Infrastructure, Community, and Governance

Post Offices in the United States are all built with the same general purpose in mind—the distribution of information and objects. Even with these identical missions, these buildings are a representation of the era and region in which they came into existence, and represent the ideals and aspirations of their time. They serve as local landmarks, community centers, and historical buildings. Vital to the communication infrastructure, yet like other forms of societal substructure, they are often treated as background buildings. However, for many Americans, post offices are the closest they get to interacting with the federal government on a regular basis.

As a Network

The networks that are a part of daily life are frequently forgotten. From transportation systems, utilities, or the postal service, these pieces of infrastructure are vital for the country to function. For example, the postal service delivers more than just mail; they help with the distribution of food stamps and covid tests, and collect voting ballots. There is an incredible and very in-depth methodology that allows the postal service to function.

The USPS is the largest postal service in the world by geography and volume, processing 47% of all global mail across 31,000 postal offices. It operates the third largest IT infrastructure in the world. Operating under a USO (universal service obligation), the USPS has a legal mandate to provide uniform prices, service, and quality, throughout the country. They are even the best face the federal government has, with a 91% approval rating.

“The Post Office is the visible form of the Federal Government to every community and to every citizen. Its hand is the only one that touches the local life, the social interests, and business concern of every neighborhood.” -Postmaster General John Wanamaker (1889)

In History

The first post office opened in 1639, and operated out of a tavern in Boston. It was the main site to pick up and drop off overseas correspondence for the entire “country.” At this point, architecture was not important to post offices, as the mailing infrastructure was set up as a small service that existed as part of a larger building or shop. The delivery system was simple: mail was tossed in a common basket or set on a table until claimed, and the receiver would pay for the postage. The writers of the constitution insisted upon the formation of a national postal system, as they thought it was vital for the spread of information. By the 1800s, there were around two hundred post offices, or spaces that worked as mail centers.

As newspapers started being transported through the postal system on the regular, horses could no longer carry enough material to be useful. Thus, trains and steamboats became the main method of transporting mail. Free at home delivery came around after the end of the civil war, and by 1890 was offered in around four hundred and fifty cities. By 1900, roughly forty-five million people were able to receive their mail delivered directly to their homes if they lived in an urban setting. Rural free delivery started occurring in 1896, and by 1912, twenty million rural residents and thirty million “village” residents received their mail directly. Parcel post began in 1913, and the need for larger spaces to sort and store packages caused a change in the layout and plans of post offices.

Rural post offices tended to be small vernacular buildings created by local craftsmen. In comparison, the United States Treasury Department’s Office of the Supervising Architect were tasked with designing the larger, urban post offices. This department worked under the Army Corps of Engineers, and were tasked with designing buildings for the government. The leaders of this department’s own architectural preferences would often seep out into the buildings they designed (especially in regard to post offices).

At the turn of the century, it was decided that too much money was being spent on building post offices (Congressmen would request large sums for post offices to be built in the areas they represented to bring in money and jobs). Thus, a new formal classification of post offices was created, which would sort the buildings into four levels by funds collected, and label what materials were allowed to be used in their design. Class A buildings had over $800,000 raised annually, and were based in major urban areas. They would have marble or granite facings, metal frames, full fireproofing, ornamental bronze work, and murals. Class B were labeled as “first class post offices,” included a yearly monetary amount of $60,000-$800,000, and were located in relatively major areas of real estate. These buildings could have limestone or sandstone facing, a wooden frame and interior elements, and iron ornamentation. Class C buildings raised $15,000-$60,000 annually, were allowed to be created out of brick or stone, and had further restrictions on what materials could be used in public spaces. Finally, Class D buildings, which included all post offices that had under $15,000 in yearly income, were to be made of brick, only required the first floor to be fireproofed, and tended to be ordinary buildings located in small towns.

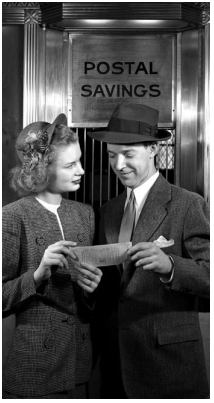

Parcels and the increase of popularity of the mail order system forced post offices to increase the amount of available storage space. At this time, post offices also served as banks for small savers. During the Great Depression, there was a rise in accounts in the Postal Savings System, as it was considered trustworthy, leading to around 770,000 total accounts during the decade. The federal building program that occurred due to FDR’s New Deal brought with it the building of countless post offices across the country. They became a widespread symbol of the federal government, and brought employment with them. The post offices built during this time tend to be decorated with commissioned murals.

In the late fifties, it was decided that too many of the post offices looked the same. While some appreciated this uniformity (the USPS), the Eisenhower administration wanted change. Working together, it was decided that there would be a standardization of interiors to eight distinct types, and the exteriors would be less regulated (and the USPS provided examples of appropriate exteriors). This compromise was done to create reasonable levels of standardization, while still recognizing the importance of allowing individuality in different contexts and climates. These post offices were referred to as the “thousand series,” and with them came the standardization of walls of letterboxes, a separation between public and private, and a service counter that is still seen in modern post offices.

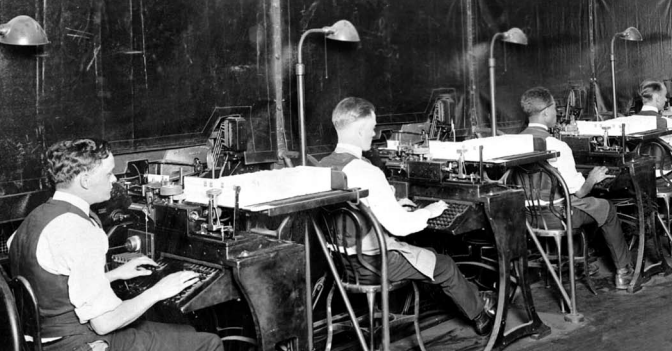

In 1971, the United States Post Office Department was renamed as the United States Postal Service. The Postal Reorganization Act in the same year brought major changes to the system. The department was allowed to further mechanize their process, collective bargaining for postal workers was legalized, the postmaster general was not longer a part of the presidential cabinet, political patronage was removed, and the USPS was given federal tax subsidies.

Currently, there has been a switch from smaller local post offices, to operating out of larger centralized “Sorting and Delivery” centers. These distribution hubs are located mainly in suburban areas, and around sixty of these “mega plants” are currently being instituted.

Are post offices more than the functions they serve? These buildings last for decades, for even as society changes, post offices still provide the same services. In a way, these buildings are isolated in their own form of time and space. In the older post offices, even with new counters and technology, it can feel like a step back in time, riding the line between past and present.

In the Frascari reading, he speaks about looking at the idea of details as a generator, and how they can be thought of as the smallest units in an architectural design. Considering post offices, their details both create the expected familiarity that allow users to easily understand how to function in the space even if they are unfamiliar with the building, and provide unique characteristics that allow for individuality. Details are repeatedly used by designers to combine function and representation in a visual manner.

“They are a chronicle of architecture in the seams; neither attempts at brilliance nor completely pointless tropes. They live in…the ‘liminal zone’… in between our aspiration and bald necessity. They are background buildings, but by virtue of their content they are also iconic.” -James Biber

Post Offices can truly look like anything. The Thomas P. Costin Jr. Post Office, the Galveston Federal Building, and the Old Post Office are all examples of current post offices that take the user back in time through their use of details and design.

The Thomas P. Costin Jr. Post Office Building is a historic post office in Lynn, Massachusetts. The two-story granite building was built in 1933. It features a central entry space that projects slightly from the building mass, and is as wide as a city block. Named after Thomas P. Costin Jr. who was the postmaster of Lynn, and the president of the National Postmasters Association. The interior of the building features the original marble floors, and wall and ceiling ornamentation.

Galveston Federal Building is a post office and a courthouse located in Galveston, Texas. Constructed in 1937, it is a limestone building that sits on a granite base. An example of an Art Deco styled building, it is monolithic with classical features and local materials. The building is on the same lot as the previous post office, a Romanesque building that was demolished. On the inside, the post office still houses the original terrazzo and cork floors, bronze ornaments, and marble and wood walls.

The Old Post Office in Washington, DC is a good example of how post offices can connect the past and the present. It was constructed in the 1890s, and was the first federal building on the main area of Pennsylvania Avenue. It housed the postmaster general’s office and the headquarters of the US Postal Offices Department till 1834, and was a functioning public post office till 1914. The building has served as the headquarters for countless federal departments, including: the departments of Agriculture, Justice, Interior, and Defense; the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Interstate Commerce Commission, and the Smithsonian. As an example of Richardsonian Romanesque Revivalism, the large steel building had a public facing clock and its own power plant. While it was almost immediately disliked by the general public due to the Neoclassical style gaining in popularity, eventually public favor changed, and now it is a powerful visual representation of history.

Post Offices are a symbol of governmental power, a representation of individual community, and a vital piece of infrastructure. They all function as a physical demonstration of an invisible hub and network transportation web. Post Offices represent stability, offering connection to rural areas and supporting the populace down to the level of the individual. Through the use of common details that illuminate the expected activities that occur within these spaces, Post Offices are standardized to a level of familiarity. Yet it is also the use of details that takes these consistent buildings and inspires contextual creativity. It is this combination of the expected and the peculiar that allow these structures to reflect the past and the present.