The De-portables of Patras

[Fragments from the Field]

PORT OF PATRAS - GREECE. The deserted industrial zone along the coast sprawls lethargically under the bleaching midday sun. As we drive on the empty road - save for the occasional stray dog and youth on mopeds - the decrepit smokestacks of Piraïkí-Patraïkí emerge, followed by the skeletal tower with the factory’s name in fading bold red lettering.

Piraïkí-Patraïkí was the flagship textile industry of Greece from 1919 until 1996 and a leading export company of supreme quality, when it was forced to closure – prey to paradigmatic murky Greek political interests and all-around scandalous mismanagement. Its disused premises now lie wrecked, yet not entirely abandoned: Hundreds of migrants from Asia and Africa find shelter in its vast halls the past few years, when Greece has emerged as a major migration entry point into the EU.

They are all men between 15 and 45: “You will not find any women here. No, never. Commando. This is commando life we live”. And it is. Migrants here wait, day after day for months, or years, for that one chance to creep, or pay, their way into or under a lorry leaving Greece for Italy; to sneak into a ferry while the guard turns the other way; to be that lucky one among the two that are allowed to leave each day while the authorities will look the other way: “the army at the new port has told us ‘two a day from you can go’”.

Migrants are a usual sight along the seaside avenue. They walk the length of the port’s outside fencing and stop every now and then. They climb up and peek in. If the site is clear, they’ll jump over and dart. It is a well-rehearsed choreography, between everyone involved, which is performed several times a day, over months on end. If they’re caught, they’re thrown out. They might engage in bloody brawls with the truck drivers who risk hefty fines and suspension of their licences if caught with human cargo, even if unsuspecting. If they do get in a truck they’ll then be loaded onto ships. Making it across the Adriatic though, does usually amount to much in itself. More often than not migrants are detected by the Italian authorities and sent back on the next boat to Patras. In less than 48 hours they have returned back to the factory. Back to square one. Next day they’ll take a stroll down the fence again.

Migrants here make home, even if temporary one, among the industrial rubble, piles of garbage, roomfuls of behemoth vintage machinery, the nature that orgiastically takes over through the broken windows and the cracks on the floor.

There is a windowless, neatly arranged sleeping room with a curtain for door. An orderly, fully-carpeted prayer area. Shoes are piled outside. We stand at the threshold and, as women, we do not enter. Men from Sudan sit cross-legged on the floor reading the Quran, or lean against the wall gazing away. Others recline on the window frames and idly take in the view of the gleaming afternoon sea, the anchoring ferry boats. There is hardly any other past-time around here. I look outside too. In the middle of the courtyard, a makeshift flagpole is erected. A frayed Greek flag flaps idly in the breeze.

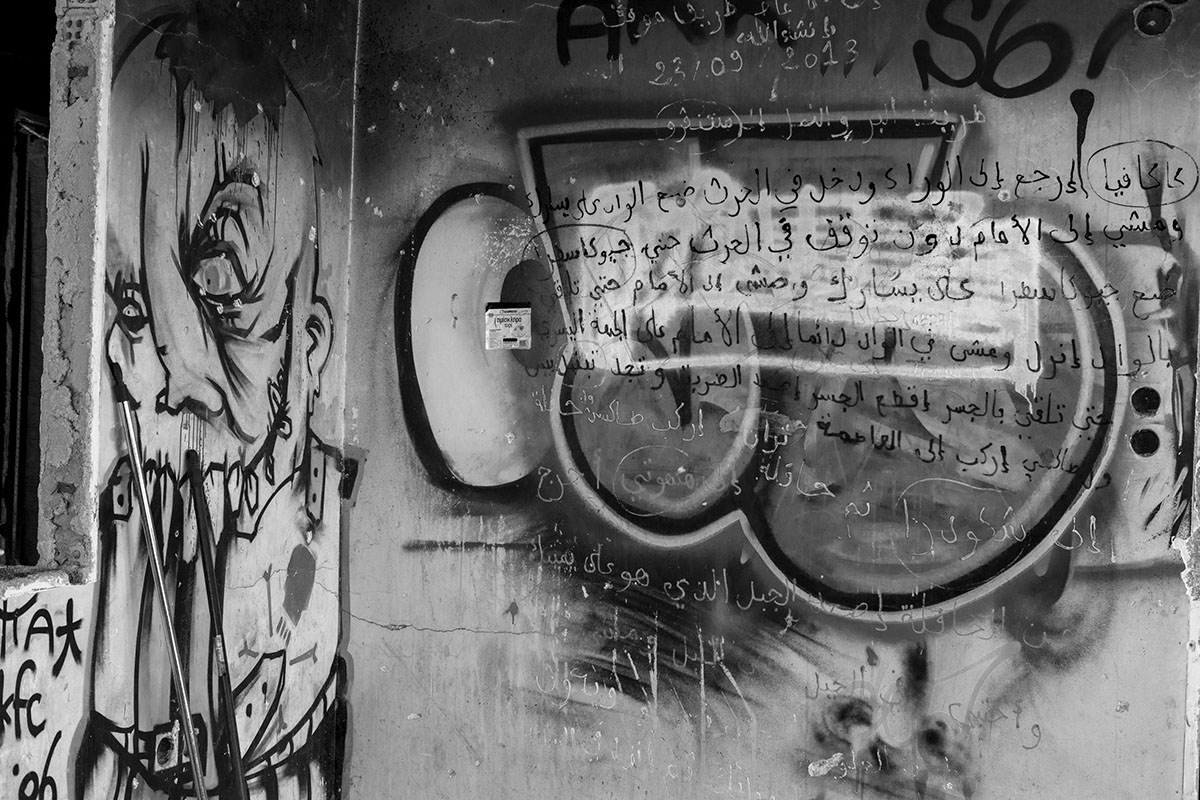

Upon the walls with the peeling paint, between the levers, the buttons, the broken sensors, you can find scribbled words in Farsi and Arabic: “I was here too”, “I wish safe roads to all the people. Ishallah”, “ Take the road to Montenegro on foot”.

In longer texts, the lettering changes into a rainbow of fashionable colours every couple of lines. Puzzled, I look closer. I was long enough in the graffiti scene to know: this is spraypaint in liquid form. You see, if you botch-open the spraypaint can with a knife, you can dip a twig or a brush in the leftovers inside. This is usually enough to do some quick hand lettering or minor details on a piece of street art before the paint quickly dries exposed to air. The leftovers from discarded cans of the few fearless graffiti-writers that came here to take advantage of the vast wallspace were now being used to indicate the intricate way into Greece, as well as out of it through Albania. “Kakavia. Shkodra. Tepelen – take the bus, Gjirokastra, Tirana, go on foot through the forest”. Place-names circled bold, standing out. Montenegro is written again and again. “Have a safe journey”. September 2013. A roadmap on a wall by the sea. If all else fails, take the road from here. “Never lose faith”.

Pencil-drawn doves with flowers in their beaks and thick-feathered open wings, caught between intricate, sacred calligraphy “Afghani. Afghani make these” we are told. Double arrows through bleeding hearts. Names of loved ones. Email addresses. Rotting fruit and sprouting onions; razor blades and thickly smoked pots that have been cooking too little for too long on open fires. Pages torn off porn magazines. And shoes. Shoes everywhere. Stacks and piles and mounds of them. Was there ever in this world a pair made to any one of them, I wonder? It seems impossible. They seem uncountable. “These are collected from the garbage. Most are the wrong size” someone tells me. “It is important that your shoes fit you good, or you get big problem, and here is no doctor”. You scavange through what others discard until you find shoes that are your size. You rummage through lives you’re forced into until you find your own life. In the end none of it will matter. The shoes, like the layers of past lives, will be left behind. In the meantime, you will have outgrown all of them. All that matters is that you keep walking.

What I will never forget from Dachau is the mountains of shoes of all sizes of the people that had died in the camp behind a glass display. How my heart stopped for a second when I pictured them stacked in pairs next to each other, and imagined all the evaporated naked feet, and all the bodies and their naked souls that had been wearing them - the sheer number of them, the devastating loss.

There was no curator and no exhibition over there where I now stood, and glass laid shattered all around me at every step I took. I was inside the display that had somehow come to life. Where on this earth do people on the road go without their shoes? What had they transpired into? So many shoes without their feet, and could I ever put myself in them, and should I and how? Where do we ever go, and what is left of us behind? In what forgotten pile does everything and everyone end up in?

Save for the roughly 100 people spread across different buildings, the place is eerily empty. Ever fewer migrants live here nowadays, the flows being redirected towards northern Europe from other pathways. Indications of their formerly crammed cohabitation are visible and viscerally felt everywhere.

Ivy is crawling up the smoked walls and clothes are drying on high-tension wires. Organic ghosts. Superimposed layers of the leftovers of decades of others’ being. As we walk across the empty dark halls I think of the hi-tech sensors inside Anna’s camera as she clicks away next to me with her delicate fingers: Could any exposure settings –ever– capture the phantoms that still linger in this room? Could any words I may –ever– write describe the intensities pressing upon our chests, pumping into our bloodstream, crumbling under our feet, pouring down through our nostrils – the human stench, the fecund soil, the lingering smell of motor oil?

We descend in the pitch black basement – the size of a football field, I’d swear- and I squint. A shiver runs down my spine, maybe it’s the sudden drop in temperature. Or not. A flood of sunlight pours through an opening where the ceiling had collapsed at its far end. Two wimpering puppies stagger through the rubble coming reluctantly towards us. A homely, rickety living room is set center-stage under the light, in a clearing among the garbage, among the floating specks of golden dust. I feel I’m floating inside a snowglobe. Shaken, Still settling. In awe. “Welcome to the American living room” Mohammed tells us and sinks into the armchair.

I’m drifting in the soothing amniotic awareness that everything and everyone around me is part of a much larger project than they or we, could ever suspect.

All you have to do is look.

All you have to do is pay attention.

Text: Joanna Tsoni

Photos: Anna Pantelia

Hundreds of migrants from Asia and Africa find shelter in its vast halls the past few years, when Greece has emerged as a major migration entry point into the EU.

The leftovers from discarded cans of the few fearless graffiti-writers that came here to take advantage of the vast wallspace were now being used to indicate the intricate way into Greece, as well as out of it through Albania. “Kakavia. Shkodra. Tepelen – take the bus, Gjirokastra, Tirana, go on foot through the forest”. Place-names circled bold, standing out. Montenegro is written again and again. “Have a safe journey”. September 2013. A roadmap on a wall by the sea. If all else fails, take the road from here. “Never lose faith”.

Here the immigrants are washing their clothes and shoes.

There is the only source of drinkable and clean water which serves at least 50 men,

Among many discarded things a ripped Holy Bible in german was left on the windowsill.

This is the scar after the acccident which this algerian immigrant had when he was intentionally hit by a car. He stayed in hospital for more than 6 months.

Stealing electricity from the columns that provide electricity to the municipality is a fact during the financial crisis. This construction has been made by immigrants in order to charge their mobile phones.

Pencil-drawn doves with flowers in their beaks and thick-feathered open wings, caught between intricate, sacred calligraphy “Afghani. Afghani make these” we are told. Double arrows through bleeding hearts. Names of loved ones.

“Welcome to the American living room” Mohammed tells us and sinks into the armchair.

A flood of sunlight pours through an opening where the ceiling had collapsed at its far end

Through this hole all the immigrants are escaping by jumping in case police raids.

Piraïkí-Patraïkí was the flagship textile industry of Greece from 1919 until 1996 and a leading export company of supreme quality, when it was forced to closure