MULTI-MEDIA DESIGN

Remote Indigenous Australian’s Access to the Education System

The inequalities continually faced by Indigenous Australians within contemporary society are in stark contrast to the egalitarian reputation Australia prides itself on. This is particularly signposted by the under-representation of Indigenous Australians within educational statistics. That is, the data released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), that highlights the pronounced discrepancies between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous educational achievements. This discrepancy is further exacerbated by degree of individuals physical remoteness (ABS, 2011).

The opportunity-oriented perspective of inequality acknowledges that the contingent circumstances of birth influence one’s opportunities and that, “equality of opportunity requires a fair starting point” (Depart of Economic and Social Affairs, 2015). Aspiring to create this fair ‘starting point’ for Indigenous people, the Australian Federal Government has legislated for greater educational equality. In December 2007, the Council of Australian Governments [COAG], “agreed to a partnership between all levels of government, to collaborate with Indigenous communities” and work towards greater overall equality (Council of Australian Governments , 2018). Thereafter, COAG established the National Indigenous Reform Agreement, “to frame the task of Closing the Gap in Indigenous disadvantage in Australia” (Ibid). This agreement is inclusive of improving educational attainment rates amongst the Indigenous population, however, in actuality, its effectiveness has been questioned regarding those living in remote communities.

Although education is the fundament of human development and life opportunities, “Indigenous Australians continue to be the most educationally disadvantaged group in Australia” (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2007). Professor Johanna Wyn from Melbourne University posits that what is acknowledged by governing bodies as a ‘gap’ in education is rather, “a measure of an educational ‘debt’, incurred through past deficits that have been historically and systemically incurred through social exclusion and poverty” (Wyn, 2009). The inequality in educational attendance is highlighted in appendix 1, where in 2017 between years 1-10, 38% of Indigenous students living in remote communities compared to noteworthy 75% of non-Indigenous students were attending school 90% of the time (PMC, 2018). This discrepancy is further evidenced by the year 12 attainment rates as demonstrated in Appendix 2. In 2019, approximately 90% of non-Indigenous students living in remote areas completed year 12 compared to that 50% of Indigenous students (ABS, 2019). These statistics epitomise the structural inequality Indigenous Australians living in remote communities are subjected to.

Martin Nakata and Linda Tuhiwai-Smith, Indigenous researchers in the postcolonial tradition, account this to the lack of cultural responsiveness required for Indigenous students to succeed (Perso, 2012). They argue that national and international assessment regimes privilege “the knowledges and practices of the Western middle class and, in doing so, marginalise Indigenous knowledges and practices” (Perso, 2012).

Given that, for many rural Indigenous Australians, “formal education has either been absent or has involved an emptying out of their own cultural heritage” (Hogarth, 2015), there has been a lack of involvement of Indigenous parents and communities within educational institutions. As these primary agents of socialisation do not value western education, education is not perceived as a cornerstone to greater life opportunities and is thus not reinforced by Indigenous parents or communities. This is reflected in the disengagement of rural Indigenous people which, in turn, perpetuates the belief in the inevitability of the status quo and maintains intergenerational cycles of socio-economic disadvantage. Johanna Wyn’s notion of historical and educational ‘debt’ aligns with this idea, in that Indigenous peoples have been unable to accrue the cultural capital valued by the society they have been culturally assimilated into – thus, increasing intergenerational trauma and hindering their life opportunities (Breen & Rottman, 1995).

Design Solution

Multi-media design can be used to combat the educational inequality rural Indigenous Australian’s face as outlined in this report. A big part of the reason rural Indigenous Australians continue to have the least access to education compared to non-rural, is because they do not have regular exposure to inspiring examples of successful role models. The implementation of promoting successful Indigenous Australians is imperative to promoting the belief in social mobility but more importantly the belief in themselves that they can be successful within both the education system and broader contemporary society.

High achieving indigenous role models such as successful athletes and academics are vital in the promotion of this self-belief. However, stories of everyday people achieving success in their lives can have equally high impact. A balance of high profile and everyday successful role models, coupled with an increase in the positive portrayal of indigenous people in films, on television [influencing media] and in educational resources will contribute to a greater sense of self-worth and therefore, belief – albeit subconscious – that it is not only possible to attain education but success is a realistic and achievable goal.

Paper Prototyping

FIRST DESIGN SOLUTION: POSTER

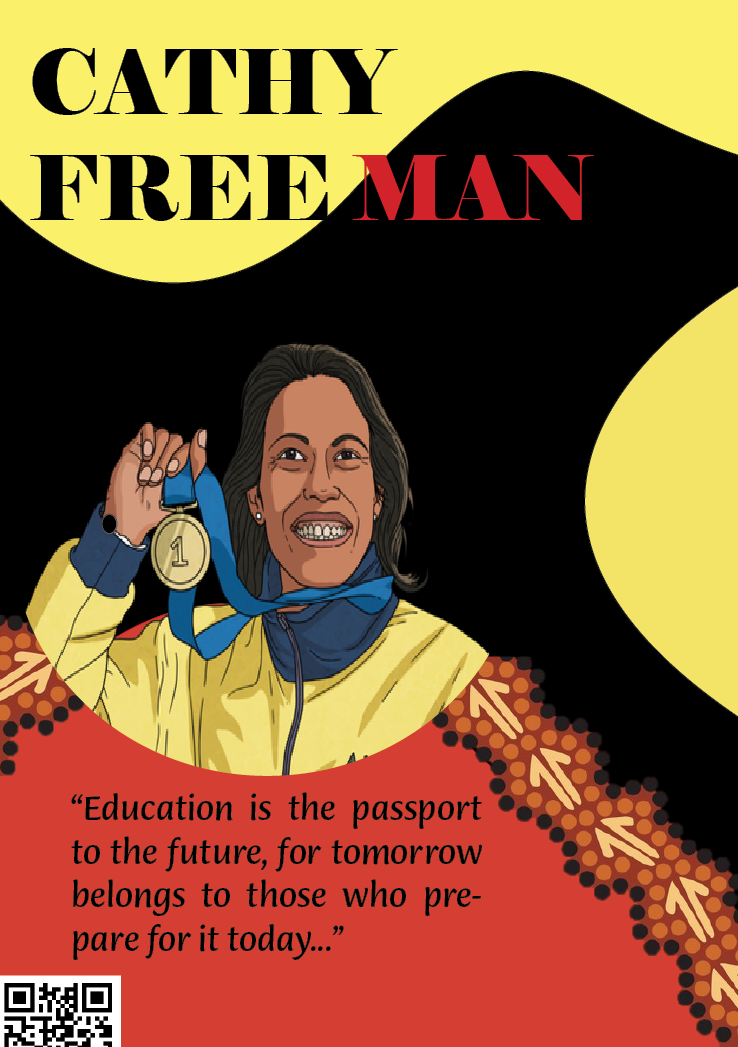

The first design concept I have gone with is a poster with a QR code that allows kids to ‘collect’ trading cards with Indigenous ‘Superheros’ on them. Firstly, the concept of the poster as a physical design solution is that different posters (focusing on different inspiring Indigenous people) would be placed around rural cities for kids to essentially hunt down and collect. The colours used throughout not just the posters but the digital design solution resemble that of the Aboriginal flag. By implementing these colours, it clearly acknowledges Indigenous culture and allows the target audience to identify and engage with the design. The rounded lines and colour blocks were also used to reflect the abstract and rounded shapes traditionally used in Indigenous artwork – as opposed to formality and rigidity that can inform certain posters. I also implemented more traditional dot and animal track artwork to better identify with the Indigenous culture and thus, foster the feeling that Rural Indigenous Australians can continue to maintain their culture and that is it widely accepted (an issue that was address in assignment one). I decided to use Cathy Freeman as the inspiring example because she is a well-known, successful Indigenous athlete that younger children can identify. This idea of Indigenous heroes could be extended to use figures like Linda Burney (potentially a harder candidate to identify as a child) exemplifying how this design solution could be developed further to education children on the very people who are shaping their lives. These figures have also been cartooned to better target the younger audiences. Beneath the cartoon, is a short quote about education to encourage young children to follow their dreams and to capitalise on education as a means of doing so.

SECOND DESIGN SOLUTION: APP

I also included a basic digital design – that is, a simple app designed for card collecting in relation to the poster. Again, this uses traditional Indigenous colours so that the target audience can identify with and relate to the design. The digital design has a basic layout for ease of use and alongside the implementation of posters with QR codes around rural towns, fosters a greater element of engagement as children have a natural desire to explore interactive cellular media.

THIRD DESIGN SOLUTION: COMIC/ NEWSLETTER

While newspapers generally don’t target younger audiences, capitalising on the comic section to romanticise, celebrate and idolise Indigenous heroes throughout history could be impactful as, just like Indigenous culture, we are portraying a message through a form of storytelling.

As discussed in class there is the possibility that newspapers may only include specialised information (less accessible, harder to personalise). Therefore, my main design is a school newsletter featuring a ‘comic of the week’. Generally, school newsletters are given out or emailed to parents and students meaning the comic would be able to reach the specified target audience. I also included the original newspaper design as well.

I decided to use the cartoon character ‘Thylacine’ as after some research I found that she was one of the few Indigenous superheros. Thylacine was designed by artist Bruno Redondo and comic book writer, Tom Taylor. Her background is a “Ngarluma hunter from the Pilbara”. The Ngarluma are an Indigenous Australian people originating from the western Pilbara area of northwest Australia. Thus, this superhero is someone who rural Indigenous Australians can identify with as she herself is from rural Australia. The use of school newsletters and newspapers as a generic form of advertisement is effective in normalising Indigenous Australians within everyday culture. The more they are promoted, the less rural Indigenous Australians may feel ostracised. By nurturing feelings of acceptance, so too does it nurture one’s self-belief to succeed in various aspects of their lives, such as education.

Combined, these elements can enhance and normalise the presence of successful Indigenous Australians to inspire and motivate younger generations. The ever-evolving nature of inequality in society reinforces the need to monitor and review current policies to strategize for a better future. In order to redress the educational debt incurred by the mainstream culture, such design solutions must be acted upon to ensure the positive development of society.

All three Designs:

Video Prototype of App