Map the System, Written by Ashlee Ganton:

Before we begin mapping the system of Canadian healthcare in relation to Indigenous inequity and it’s outcomes, it’s important to recognize that in Alberta, we are situated on Treaty 6 territory, the traditional lands of First Nations and Metis people. It’s also important to recognize that in 1876, the Canadian government came to an agreement and promised to provide the storage of a medicine chest clause. Treaties 1 through 5 unfortunately didn’t include this. The medicine chest clause, in modern terms, could be translated as a promise to equal and full access to healthcare. Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris is remembered for saying “What I trust and hope we will do is not for to-day or tomorrow only; what I will promise, and what I believe and hope you will take, is to last as long as that sun shines and the yonder river flows" while he negotiated these terms for Treaty 6. Such promises may be interpreted as beneficial by the general public. It may seem that Indigenous healthcare, at least in Alberta, has always been universal, at least since confederation and the signing of Treaty 6. One needs to only study early Canadian history for a few minutes to know that the colonial governments gave false promises to the Indigenous people over and over again in order to manipulate them for the benefit of the Eurocentric progress.

For Indigenous people, healthcare is sacred. The process of healing has many elements, and the balance of these elements is what leads to a healthy life. The medicine wheel is an example of the Indigenous interpretation of health. The wheel has four directions, and among those directions are different elements that represent life. It represents the stages of life, the seasons of the year, the aspects of life, the elements of nature, ceremonial healing plants, and animals that represent each direction. The colours, for some Indigenous people, represent the races of the world. What’s important to note with the medicine wheel, is that any time that any of these elements are out of balance or if an Indigenous person cannot participate in the traditional healing, within their community, their quality of life and access to balanced health is already limited. The practice of traditional healing is important to Indigenous people, but it’s important to note that even though they participate in what would be considered alternative medicine, within their community, this doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t have access to modern medicine when they need it and when they seek out for it.

With the implementation of the British North American Act of 1867 and the Indian Act of 1876, the rights of Indigenous people were dismissed and the Canadian government was able to forgo any responsibility to take care of them. Both of these acts ensured to mention Indigenous healthcare, but neither of the acts actually did anything to help. The British North American act claimed that health services were of provincial jurisdiction. But that Indian Affairs was a matter of federal jurisdiction. This created uncertainty and confusion that still exists today in regards to who is responsible for Indigenous healthcare. 10 years later with the introduction of the Indian Act, new provisions were in place that mentioned that any Indigenous person who abandoned their traditional values and practices would have the right to land ownership and the right to vote. Still, even for those who did abandon their traditional lifestyle, access to healthcare was up in the air as the Indian Act didn’t specify which governmental body was responsible for Indigenous healthcare. Fast forward to 1939, there was a Supreme Court Ruling that mentioned that the Federal government was responsible for Inuit people. For whatever reason, they only specified this responsibility to Inuit people, and not the rest of the Indigenous nations of Canada. Furthermore, even though they claimed responsibility, they still didn’t mention whether healthcare was a part of this revision. 30 years later in 1969, the Canadian government introduced White Paper, a policy that sought to get rid of the Indian Act and all of it’s amendments since 1876. With this policy, rights specific to Indigenous people would have perished, and all Indigenous people would have simply just become Canadian citizens. After centuries of violence, manipulation, and the revoking of Indigenous culture, the Canadian government assumed that the right thing to do was create a policy that combined Indigenous people with non-Indigenous people. Fortuitously, creating another policy that promoted the assimilation of Indigenous people. White paper is important to mention because a year later, in 1970, Red paper was created. Red paper was a response from the Indigenous people who were exhausted and fed up with the Canadian government. The policy included revisions from Indigenous people, and explained what they needed in detail. This policy revision was thankfully accepted by the Canadian government and it was the start of a real conversation about Indigenous health care, and it required that the government mention which governmental body was responsible. In 1979, The Indian Health Policy was introduced and increased Indigenous health was finally a goal mentioned within Canadian legislation. To reiterate though, the legislative ambiguity and lack of regard for Indigenous health lasted for 112 years. Even though the Indian Health Policy was introduced in 1979, this wasn’t the end of the fight for equitable access to healthcare for Indigenous people. In 1994, the policy was revisited and renamed as the “Aboriginal Health Policy” and promised to highlight the inequities that Indigenous people face within the healthcare system. A year later in 1995, the federal government introduced the “Inherent Right to Self-Government Policy” that recognized that the inherent right to self-government is an existing Aboriginal right under section 35 of the Constitution, which once again, reinstated the ambiguity of the issue’s past.

Among all of the policies and legislations that have come and gone in Canada in regards to Indigenous health care, there are other factors that are at play. While it may seem like the Canadian government’s limp-wristed action towards the issue is enough to explain why it exists, there are other factors that supplement the issue, and keep the challenge in place. Since the creation of the reserves system in the 1850s, many Indigenous people still live on reservations, and have been forced to live a remote lifestyle. As a consequence of this, Indigenous people simply have no way of accessing modern medicine. Furthermore, due to a lack of ability to earn a sustainable income while living within the reserves system, many families live in unhealthy, sometimes crowded environments, increasing the chance of spreading disease among one another. According to Statistics Canada, First Nations communities had an average housing score of 70.6 points in 2016 compared to Non-Indigenous communities with an average housing score of 94.6 in 2016. This score is composed of two subcomponents, housing quality (not crowded) and housing quantity (not in need of major repair). While the average likelihood of living in a crowded home as an Indigenous person has decreased in recent years, it’s still more likely to be an issue for Indigenous people rather than non-Indigenous people. Nevertheless, the inequities that Indigenous people face within Canada’s healthcare system are proven to lead to an increase of disease and death. “In 2000, life expectancy at birth for First Nations males and females in Canada was 68.9 years and 76.6 years, respectively, compared to 76.3 years for males and 81.8 years for females in the Canadian population.” (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Basic Departmental Data, 2002)

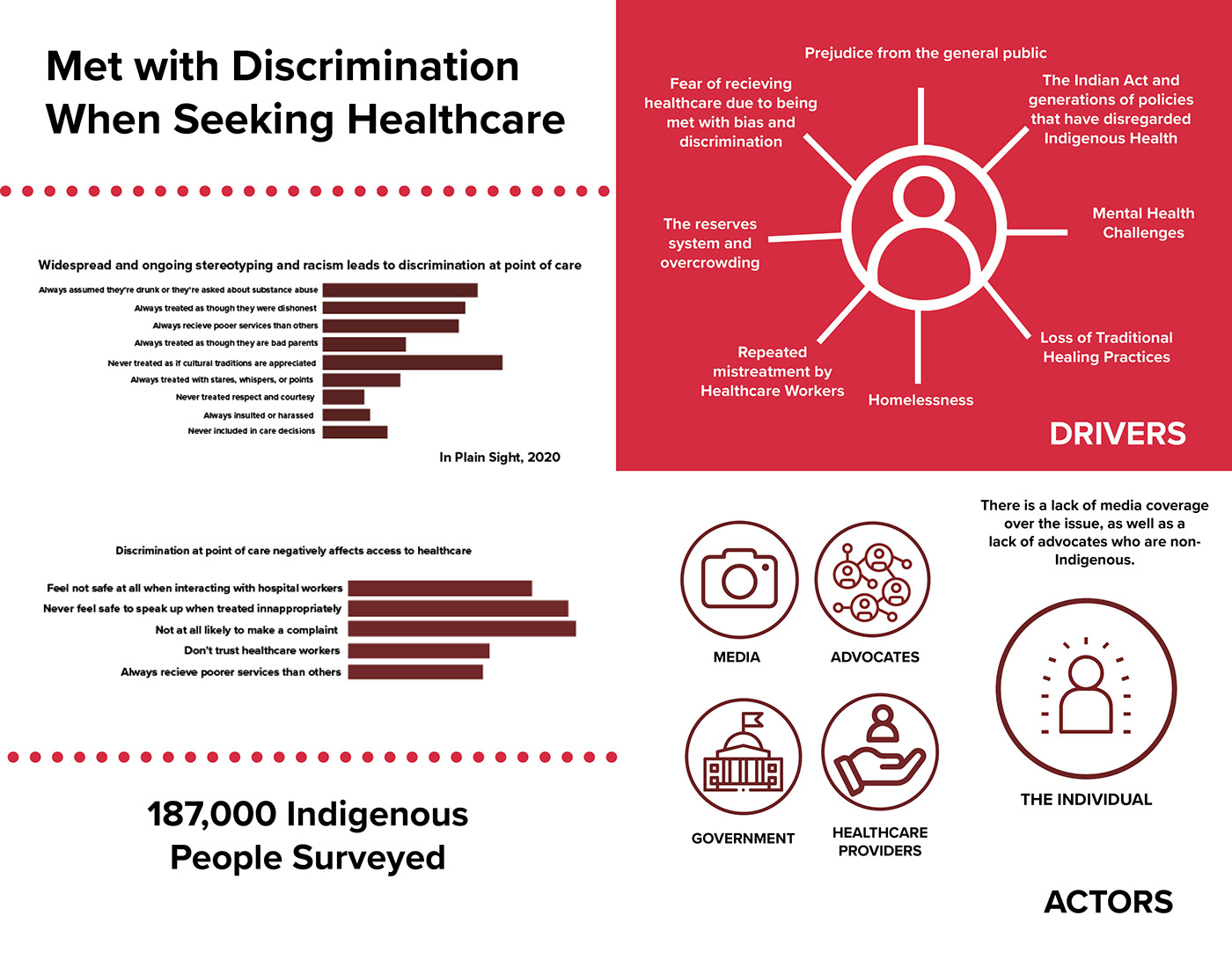

For the Indigenous people who have moved into urban areas, access to equitable healthcare is still limited even though they can hypothetically access hospitals or modern medicine within a city. Many Indigenous people have relocated to urban centres with the hopes of a better life, and the potential of a real future. Oftentimes, they’re unable to find work because of the biases held by non-Indigenous people, and they’re unable to find a sense of belonging and community. The combination of these two factors has led to the overwhelming percentage of homelessness in Indigenous populations. With the unfortunate reality that 1 in 15 Indigenous people in urban centres are homeless compared to a 1 in 128 for the general population (as of 2013), there is an even greater intrinsic bias towards Indigenous people that directly affects their ability to access healthcare. The bias is that Indigenous people are alcoholics, or drug users. In a CBC article entitled “Investigation finds widespread racism and discrimination against Indigenous peoples in B.C. health-care system” Tania Dick, a nurse practitioner from the Dzawada'enuxw First Nation and a member of the First Nations Health Council recounts the story of her aunt who faced this bias. Her aunt was taken to an emergency room after falling and hitting her head. But when she arrived, Tania said health-care staff assumed she was intoxicated. By the time they realized something serious was going on, Tania said it was too late. She said her aunt — who was experiencing a brain bleed — died while being transferred to a major regional hospital. Tania mentions that her aunt’s experience is far from an isolated incident and that this is a common story among Indigenous communities. This has happened as recently as September of 2020, the case of Joyce Echaquan of the Manawan community and Atikamekw Nation in Quebec. Joyce used her phone to record and post the racist treatment and remarks she was subjected to before her death on September 28th 2020. These incidents happen all the time and the fact that these biases and incidents happen at the hands of the nurses and doctors who are directly responsible for healthcare, proves that there’s massive inequity for Indigenous healthcare in Canada. These biases are proven to be deadly, and they are a major contributor to keeping this challenge in place.

Access to healthcare is a basic human right, but unfortunately this concept hasn’t applied to Indigenous people throughout the history of Canada. All of these inequities lead to the outcome of a higher percentage of death and disease among the Indigenous population, which is a recurring tragedy in Canada. Fortunately there are organizations that are trying to dismantle this challenge as much as possible. Most of the organizations are led by Indigenous people who have either been directly affected by this issue, or have witnessed it throughout their lives. The NCCIH - National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health, Indigenous Services Canada, Indigenous Awareness Canada, The First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), The First Nations Health Authority, and the First Nations Health Council are all directly working to ensure that healthcare is more equitable for Indigenous people in the future. Another way to solve this problem is to promote education and awareness among non-Indigenous people. If there was a willingness to access education about why the Canadian government implemented the policies that are keeping the issue in place, why Indigenous people are more likely to live remotely, or why certain biases exist, there would be an increased likelihood of solving this challenge.

Bibliography

Paradies, Yin. "Racism and Indigenous Health." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. 26 Sep. 2018; https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-86.

"Investigation Finds Widespread Racism Against Indigenous Peoples In B.C. Health-Care System | CBC News". CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/bc-health-care-racism-report-1.5820306.

"A Short History Of Indigenous Health 1600-2015". https://physiciansapply.ca/cases/case-4-indigenous-health/a-short-history-of-indigenous-health-1600-2014/.

Hick, Sarah. 2019. “The Enduring Plague: How Tuberculosis in Canadian Indigenous Communities Is Emblematic of a Greater Failure in Healthcare Equality.” Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health 9 (2): 89–92. doi:10.2991/jegh.k.190314.002.

Shaheen-Hussain, Samir. 2020. Fighting for a Hand to Hold : Confronting Medical Colonialism against Indigenous Children in Canada. McGill-Queen’s Indigenous and Northern Studies: 97. McGill-Queen’s University Press. https://library.macewan.ca/full-record/cat00565a/9245053.

Greenwood, Margo, Nicole Lindsay, Jessie King, and David Loewen. “Ethical Spaces and Places: Indigenous Cultural Safety in British Columbia Health Care.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 13, no. 3 (September 2017): 179–89. https://library.macewan.ca/full-record/edb/137592870.

Canada, Health. 2021. "ARCHIVED - Closing The Gaps In Aboriginal Health - Canada.Ca". Canada.Ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/science-research/reports-publications/health-policy-research/closing-gaps-aboriginal-health.html.

"In Plain Sight". 2020. Addressing Indigenous-Specific Racism And Discrimination In B.C. Health Care. https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2020/11/In-Plain-Sight-Full-Report.pdf