Tecla Shield | Industrial Design

Toronto, Canada - Aug 2013

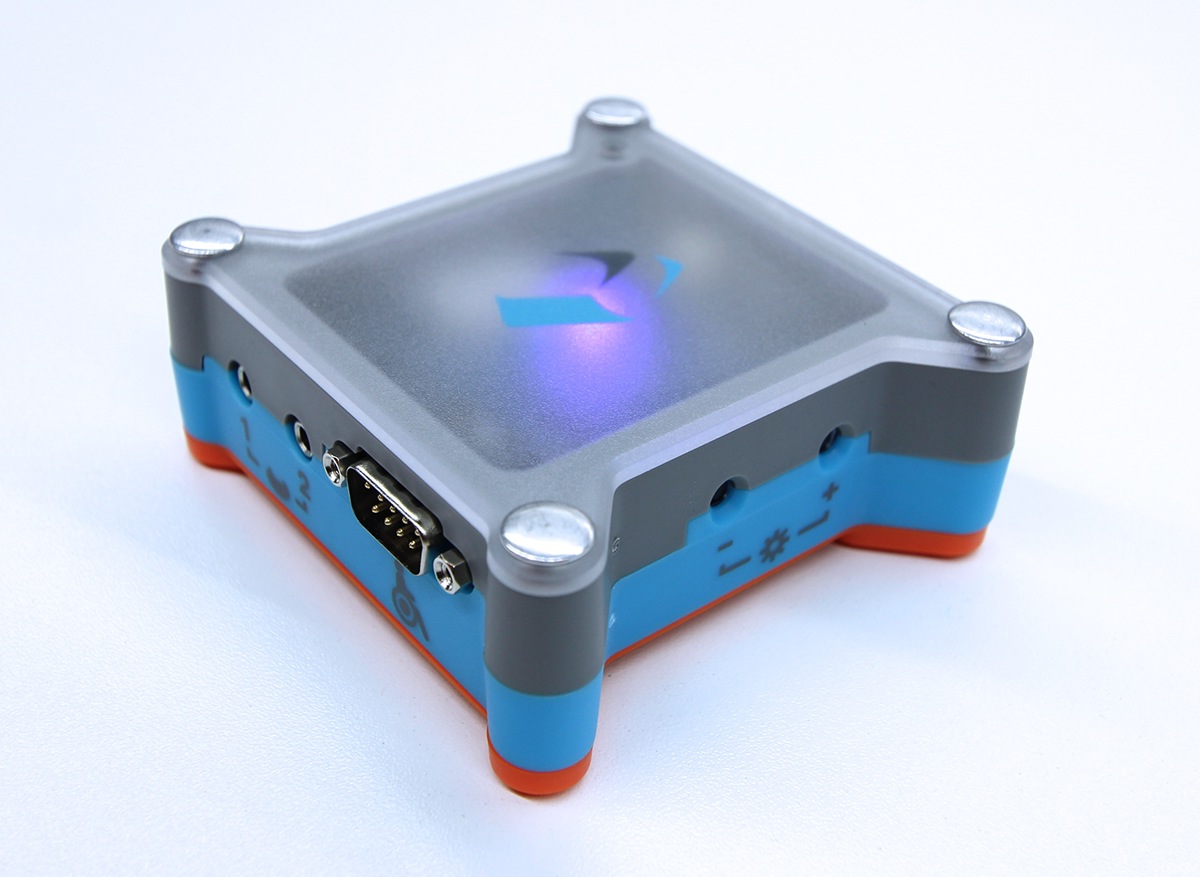

ABS plastic - 3D Printed & Injection Moulded

by Lawrence Kwok, Lead Designer | Komodo OpenLab Inc.

'The Tecla Shield DOS™ is a wireless device that lets you control smartphones and tablets using your external switches or the driving controls of your powered wheelchair.'

Komodo Openlab Co-Founder and Technical Lead, Jorge Silva approached me to assist in the design of the new enclosure for the Tecla Shield. Having already previously worked with George Brown College, he was looking to develop the concept further into something with more commercial appeal and some functional improvements, all in a low-cost niche device that would ship only 1000 units annually.

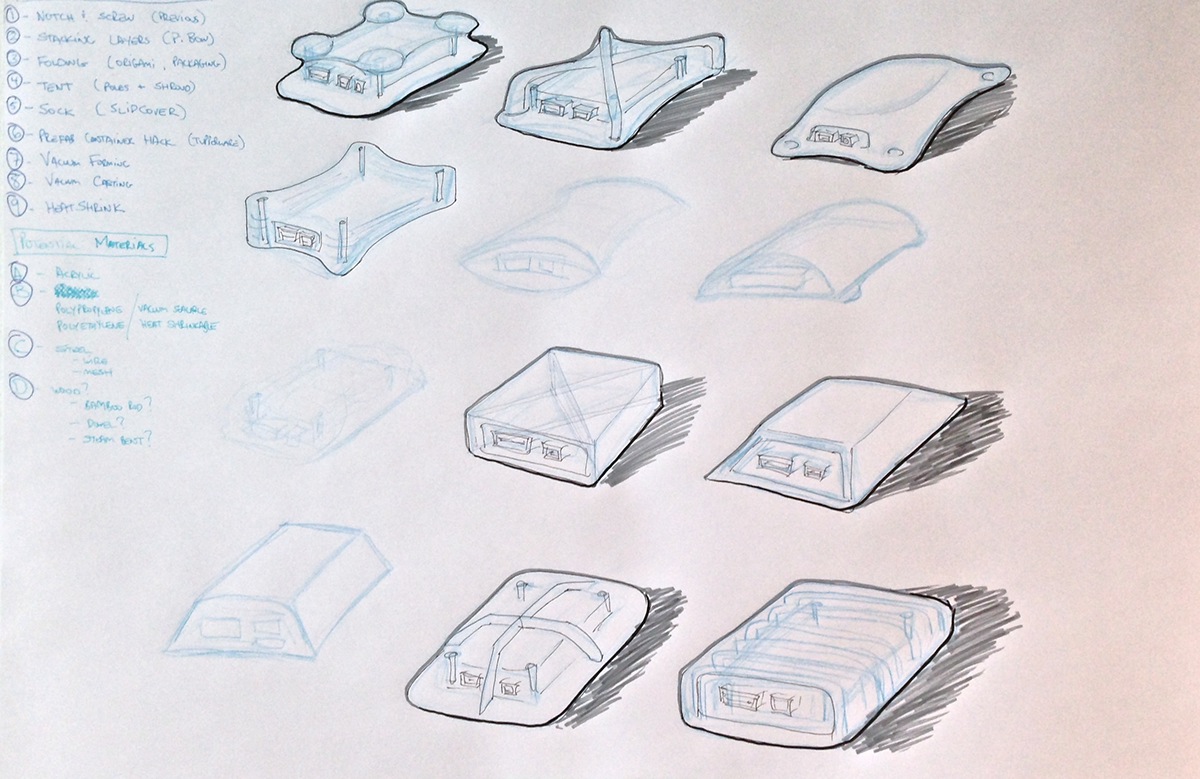

Early sketches, where I'm trying to imagine the absolute simplest enclosure possible taking into account material cost, manufacturing method, ease of assembly, durability in use and product aesthetic. Originally, I had envisioned a hard 'skeletal' frame, with a soft, malleable 'shroud', making the assembly reliable but also very simple.

Simple cardboard bounding box, attempting to come to terms with the size of the internals of the Tecla Uno and how rearranging them affects both the handling and the product perception.

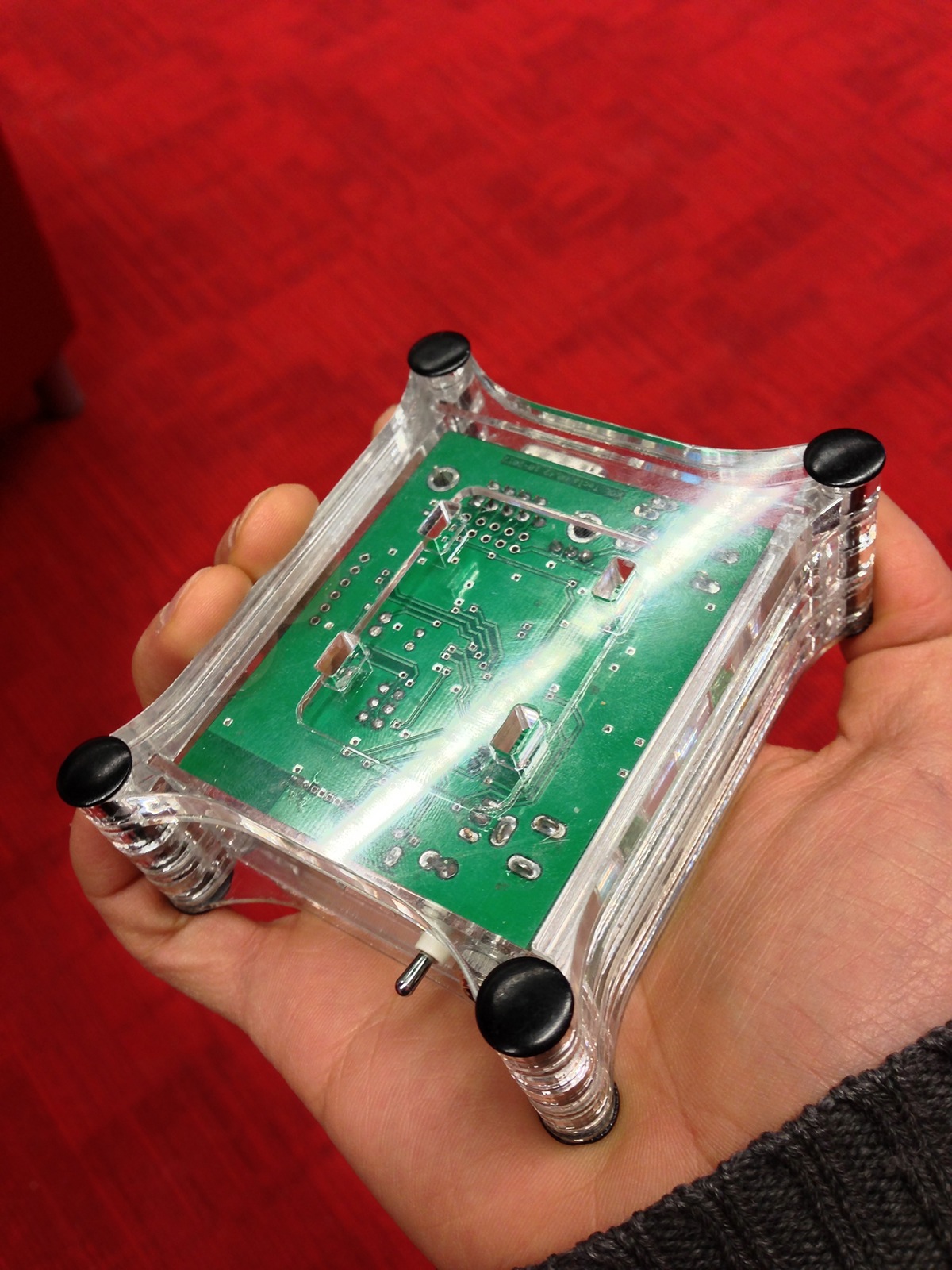

This is a previous prototype developed in partnership between Komodo Openlab and George Brown College, using laser cut acrylic. This is where Tecla's form 'DNA' originates, as well the the method of using Chicago-style screws for assembly. Anyone familiar with the PiBow case for Raspberry Pi can instantly see the similarities and inspiration.

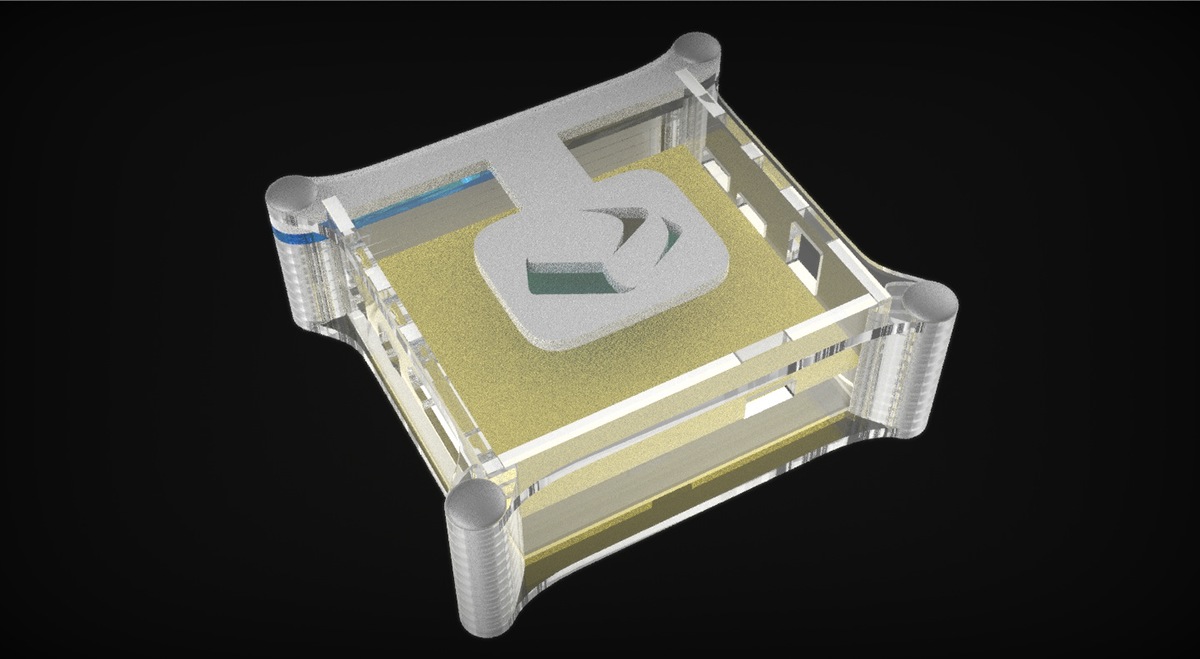

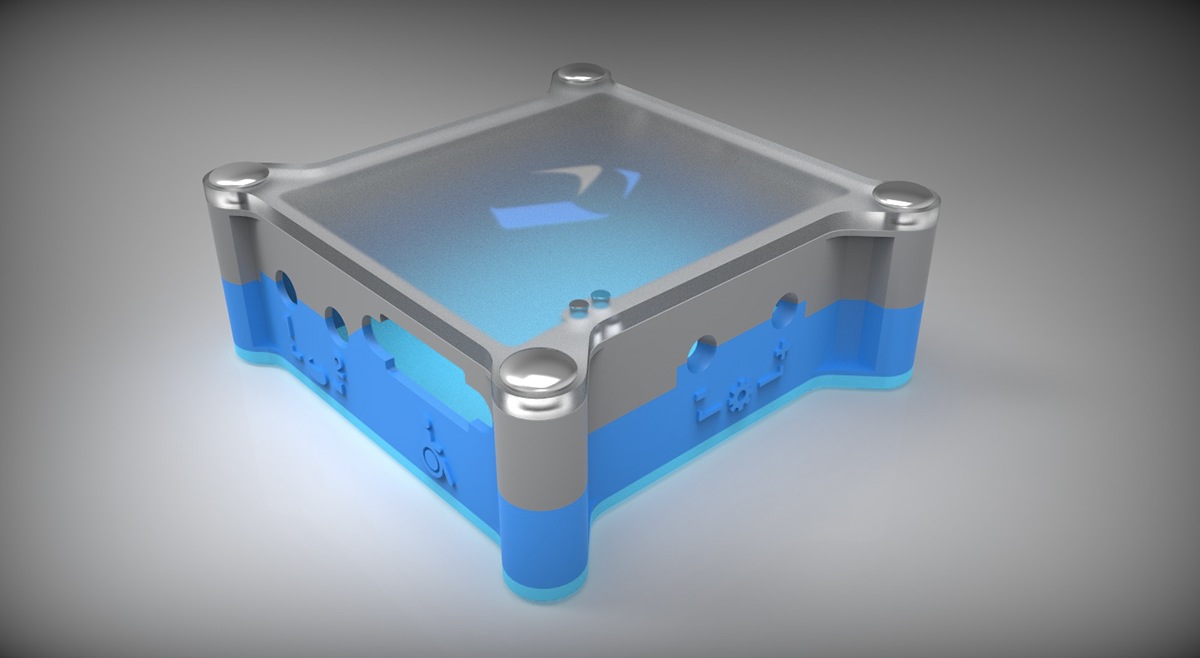

Building off of the George Brown model, I started taking into consideration brand aesthetics, attempting to use the existing material and manufacturing method to speak a more mainstream and commercial language.

Jorge wanted to explore what injection moulding would cost, so we quickly translated the model in order to obtain early quotes. The tooling required to develop a working model would have increased the cost enough for this to be a healthy indicator of what the initial investment would be.

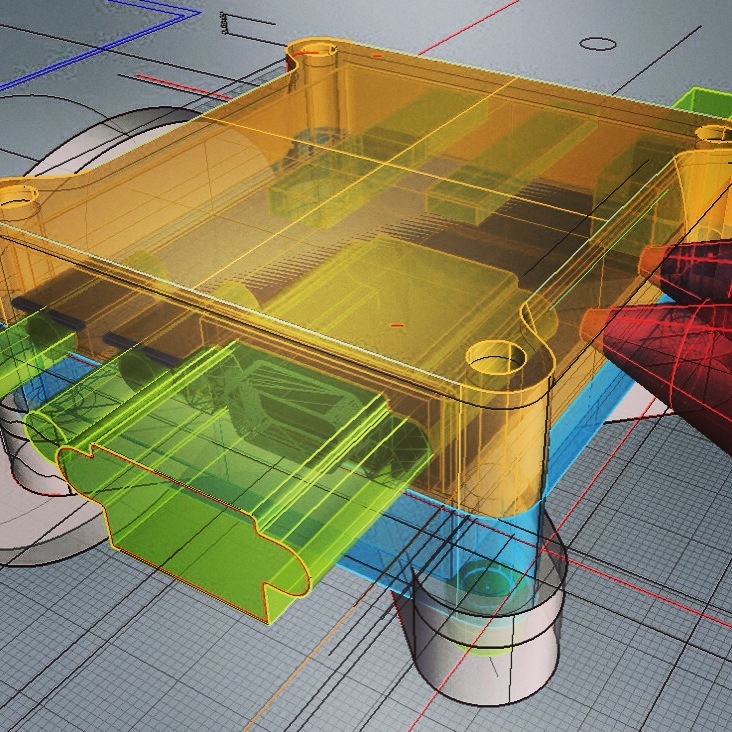

Because the electronics were constantly changing, the CAD model was made up of, 'floating' datums and volumes. This meant that anytime things changed, a new model could be generated quickly.

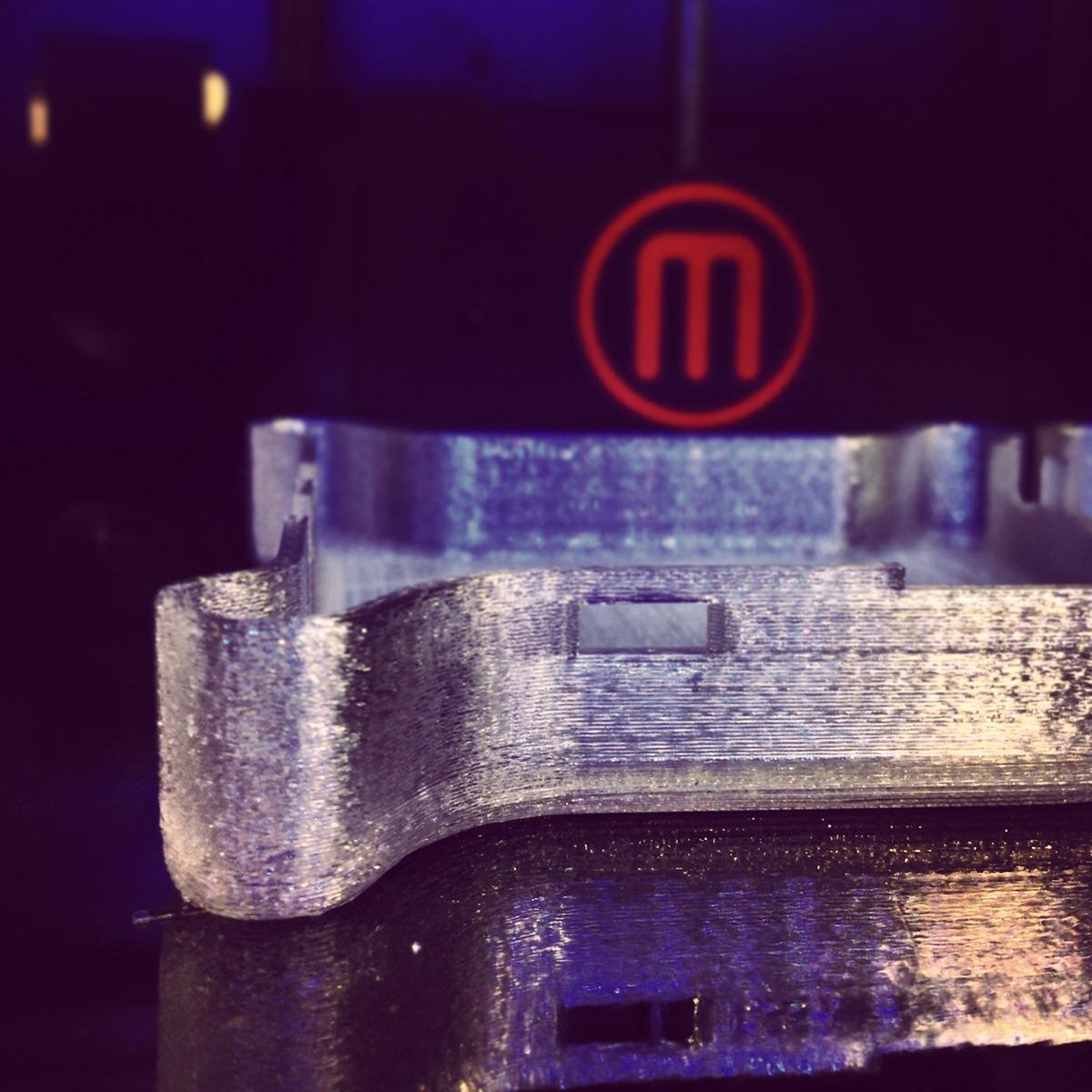

Injection molding proved too expensive at the time, so Komodo decided to buy a Makerbot for manufacturing purposes instead. This wasn't my first time 3D printing, but it was my first time operating a printer myself and blurring the boundaries between a prototype and a finished product.

Having a printer made it very easy to check the design in real world conditions, but consistency in print quality was always a concern.

I suspected that while we were pursuing 3D printing as the sole method of production, we hadn't established confidence that it would work, that at any time we could change channels back to injection moulding, so the design had to be flexible in the face of contradicting immediate concerns vs. future concerns.

One of the biggest concerns with 3D printing was quality and consistency with respect to the first few layers of the print. Surface quality, texture, flatness and build plate adhesion was a moving target. It would have taken at least 30 hours to manually develop a raft and a method for those first few layers to work properly. The Makerware software updates weren't at the point were this was a quick fix and confidence was shaky.

It was at this time that the decision was made (based on Mauricio's feedback) to deviate from the two part assembly into something more manageable for the printer, helping to decrease print times and increase print quality and consistency. Thankfully by this time, Makerbot's firmware was fast improving upon the community's (specifically, 'Sailfish') own innovations in slicing algorithms. These two events made realizing a 'finished' product much more within grasp.

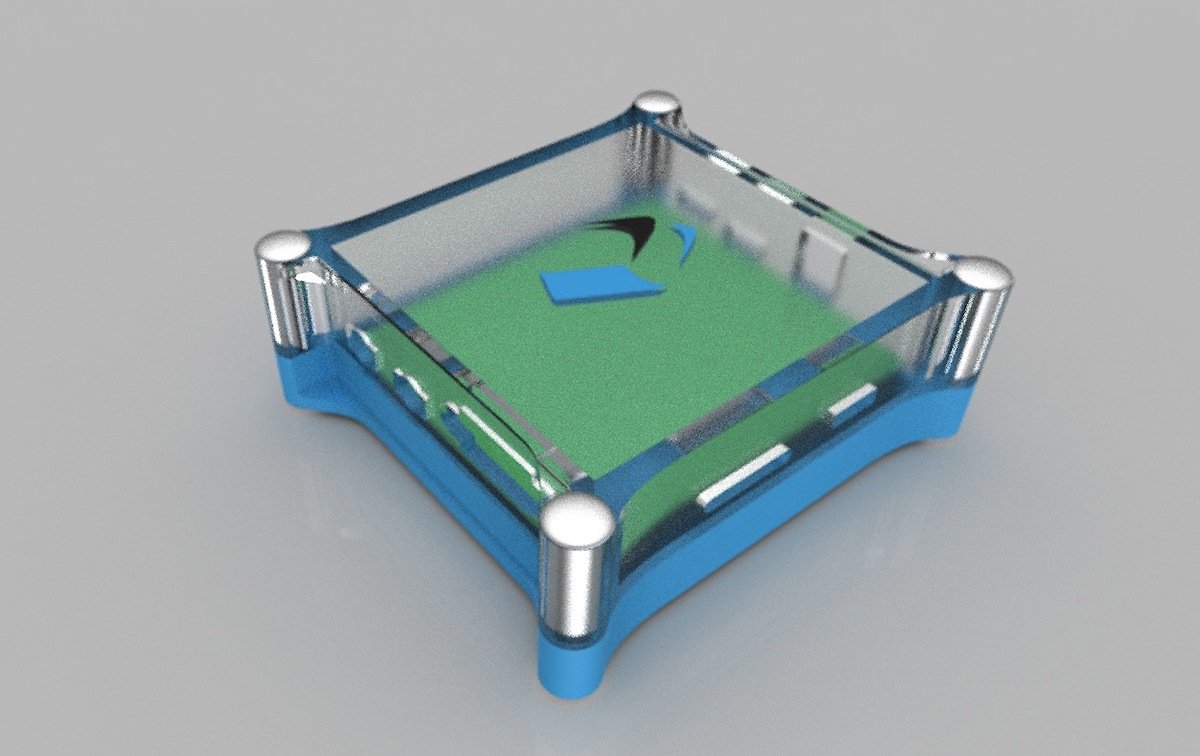

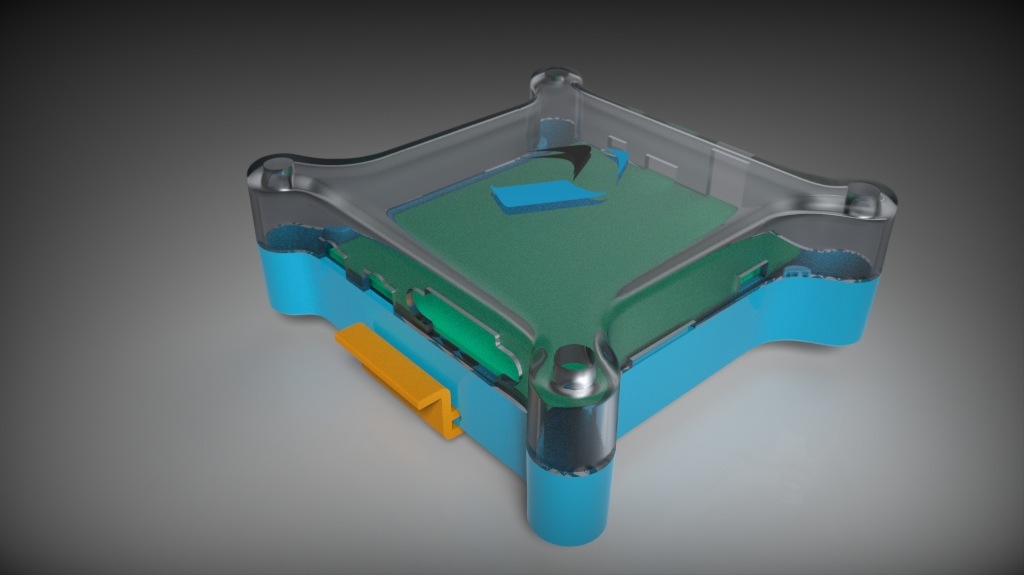

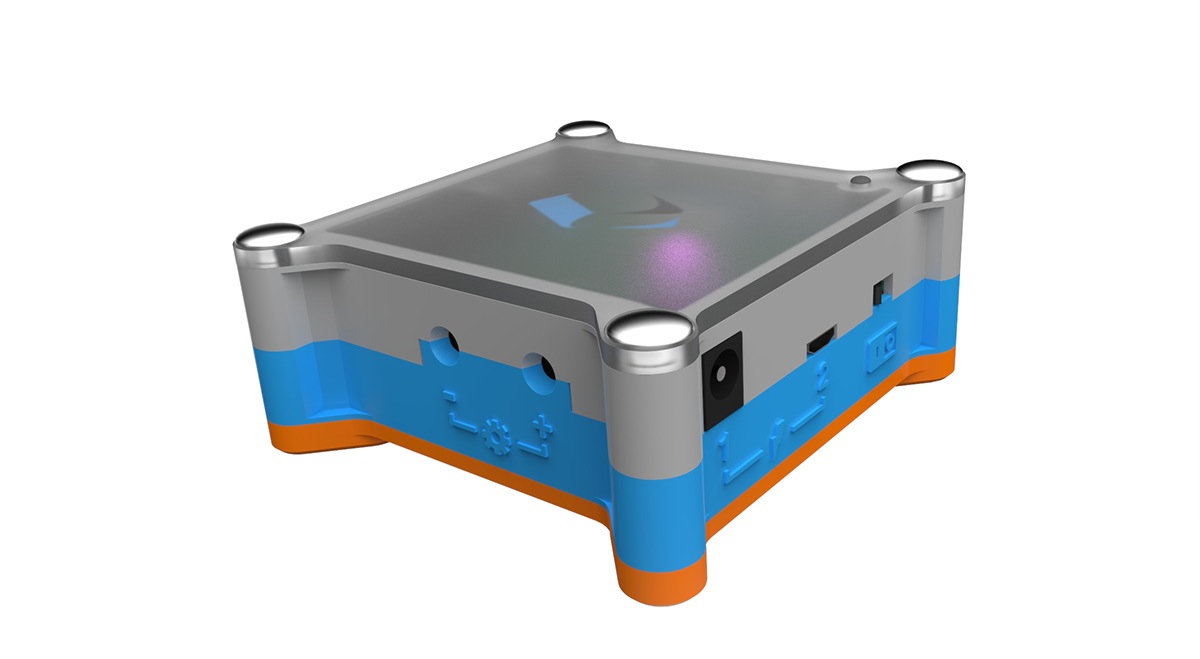

We decided to split the assembly into 4 parts, and I decided to bring the acrylic back into the equation, knowing full well that this meant we would be 3D printing AND laser cutting. The tradeoff in number of processes was made up by the fact that this was an opportunity to revisit the brand aesthetics - a return to the original PiBow inspiration, and a nod to the George Brown concept.

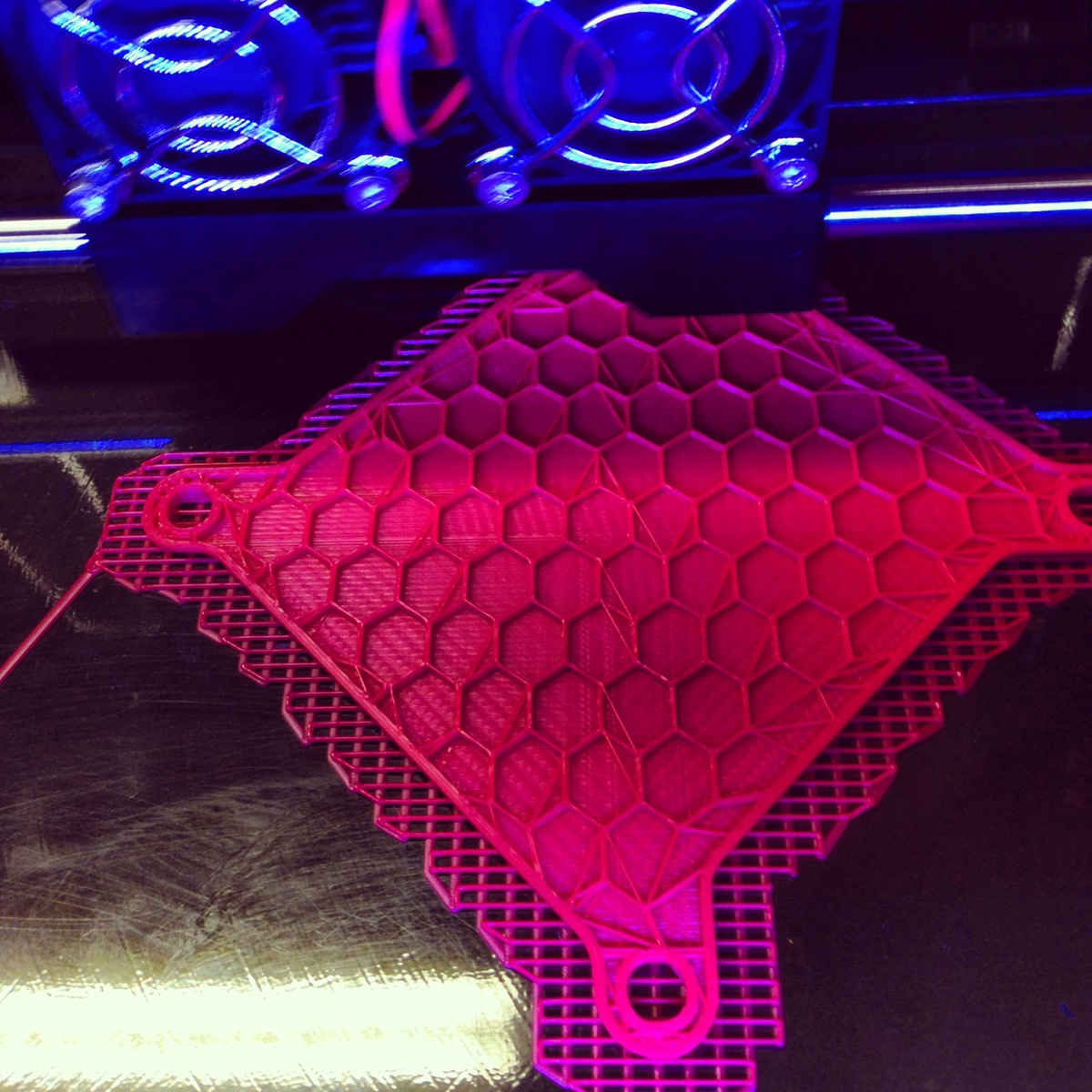

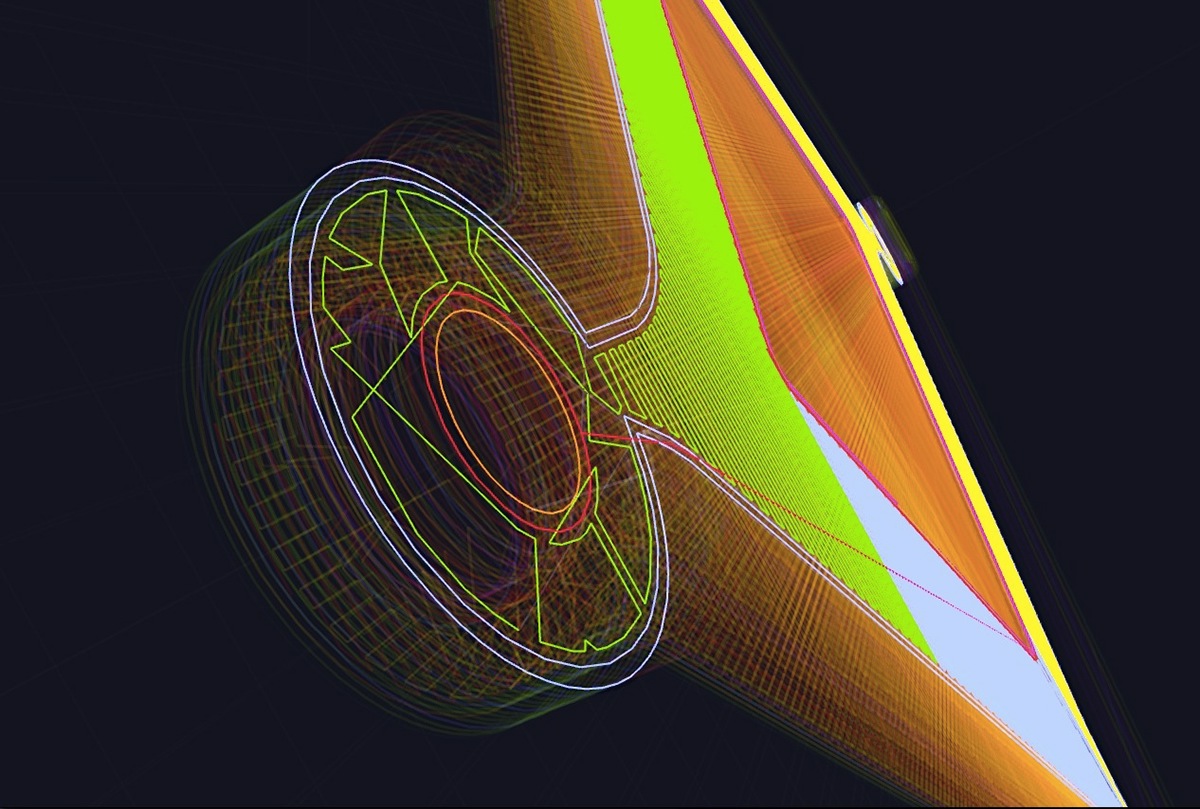

3D printing a finished product means having to audit gcode to ensure the slicing algorithm is giving you exactly the kind of structure and quality that the customer expects and that the printer can deliver quickly, consistently and reliably, while at the same time minimizing material usage and waste.

Gcode visualization is a great way to simulate what your printer is going to do line by line, layer by layer, before ever starting up the printer. You can catch trouble spots before they ever materialize, alter the printer settings in response to those errors, or any other situational constraints that may arise.

Now that I was getting good results and able to optimize print times, we were able to construct, 'Beta Boxes' for the developers, and I started prototyping the wheelchair mounting clip. Jorge came up with the brilliant idea: Who doesn't love magnets?

The target for Komodo was 100 units a month, so I sat down and calculated how much time each part needed for printing/finishing, how many parts could be simulaneously printed, how much time each unit required for assembly and testing, how many printers would be required, what print speeds were within reason, as well as how many failures to expect. It was an amazing feeling to already know all the significant numbers rather than an uneducated or abstract notion.

After considering a number of palettes based on Makerbot's own plastic selection, Komodo opted for colours that were in accordance with their brand, as well as deviated from the more, 'medical-device-looking', colours.

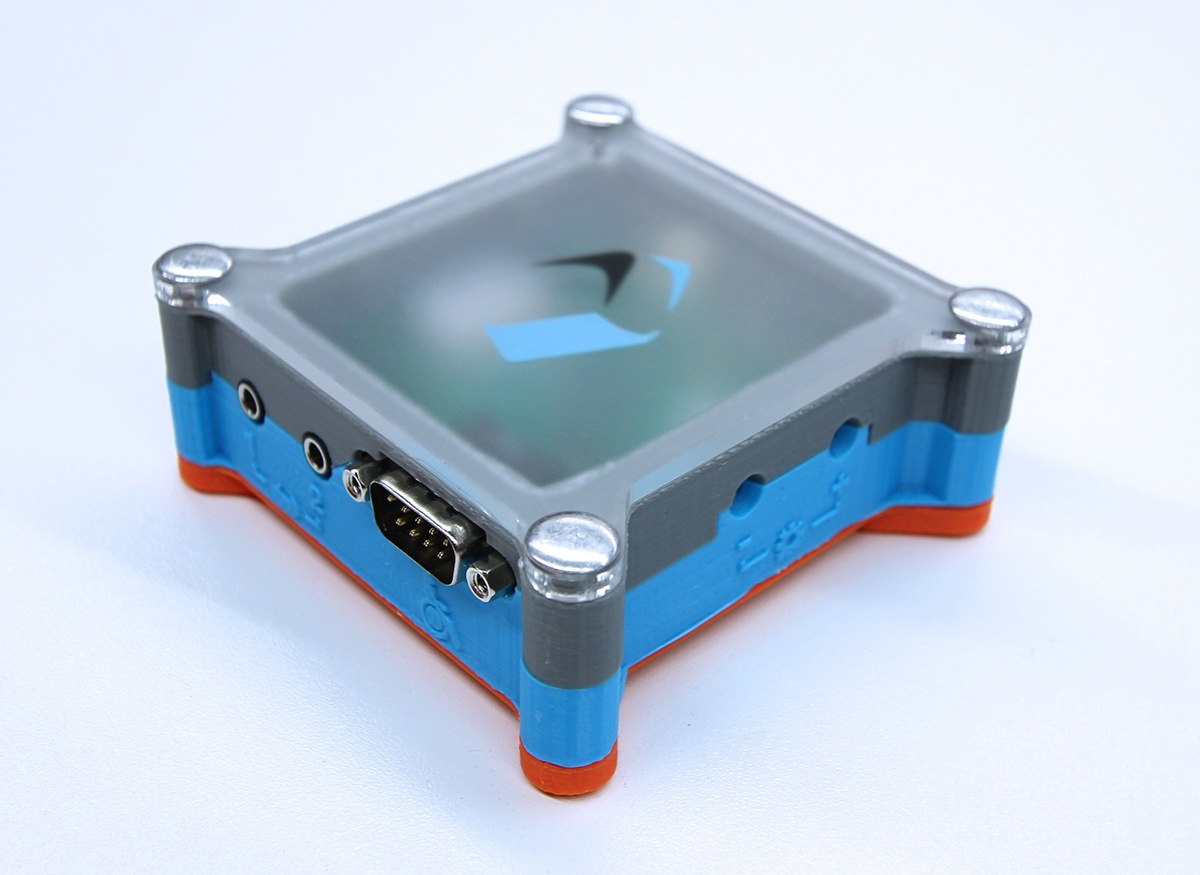

The, 'final' product. These units were considered ready for customer use. Although the 3D printer creates imperfections in each print, the nature of the design allows the materials to play to their strengths, communicating a strong sense of intent.

Having to design a prototype that functions as a final product, while also taking into consideration that the prototype method is also the production method was an amazing opportunity to think both conceptually and pragmatically.

Having an established workflow meant being able to quickly prototype/produce new accessories like this phone mount, which utlizes industrial-grade velcro, hidden from view.

Prototyping is not always a clean, linear or glamourous activity.

I believe that materials and objects communicate a lot of information, especially in their imperfections with respect to both form and function.

So things were all set to go, but new funding became available and we had to quickly pivot back to injection moulding. Because the design was made to accommodate both possibilities, it stepped back into its roll as a prototype that could be quickly translated. Due to my lack of experience with injection moulding, a professional was called in.

Stopher Christensen, Founder of Tensen Design, did an amazing job of translating the design intent and quickly refining it for injection moulding. Read more about it on Tensen's thorough blog post.

3D print on the left took 45min on the makerbot, injection mould on the right took 6 hours on the makerbot, but less than a minute in final production. The material behaves so differently in each process, but the parts perform the same 'essential' functions: Ensuring structural integrity, holding the internals firmly in place and enabling ease of assembly.

Mauricio Meza (Co-Founder and Business Development) and Jorge Silva, assembling the first production batches. The daily output of Tecla Uno was roughly 7 or 8. On the first day of Tecla Dos, these two made over 50. They now have someone dedicated to assembly among other duties.

To me, being, 'in the bubble' always involves a little bit of wandering.

You just do what it takes to get from A to B.