Aristotle once wrote that a human being can be described considering three elements or points of view: what he is. i.e. his character, his abilities, his intelligence; what he has, i.e. what he owns; what he represents, in other words how he is seen by the people around him, and therefore his fame, his reputation. Nowadays the most outstanding example of this last feature can be found, in its most straightforward, crude and nasty form, in the degree mocking papyrus. Of course one must always keep in mind the stylistic necessity of the rhyme and that while writing it down, it can happen that people get carried away and go down a little heavy on things, putting a lot of emphases (a.k.a. vulgarity) on the intimate (read, sexual) aspects of the graduate’s life; nonetheless the papyrus can be considered the most transparent representation of what the graduate has shown of himself/herself.

In addition to having the protagonist think about the concept of friendship and informing the relatives that studying was not the graduate’s priority during his college years, this funny paper is the master column of any noteworthy graduation after-party ceremony. The degree papyrus, final act in a student’s life, is the last goliardic outburst before (hopefully) entering into the working life which requires seriousness (at least as far as the public role of a person is concerned). The papyrus dates way back; it is the heirloom of an ancient ceremony still alive today, even though it has gone through many updates and mutations during the past decades.

I looked deeply into this matter to find out what kind of developments the papyrus experienced throughout the centuries and I realized that its evolution runs parallel to that of the History.

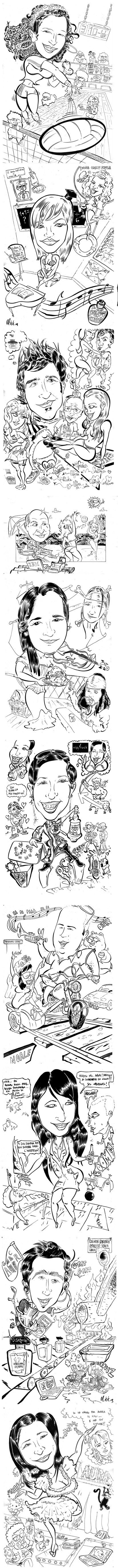

There are testimonies that go back to an era before the modern goliardic was born; they testify the habit of informing the whole community of the graduation event by hanging on a wall manifests containing sonnets, epigraphs, and inscriptions of various kinds. These papers were very much different from the modern papyrus, since the rhetorical content was one of the moral and intellectual exaltations of the graduate, while at the same time totally omitting the light aspects of his life. The point that matters is that, even in these first specimens of papyruses, it is the written part that plays the primary role aside from the presence of a few typographic decorations, and the goliardic life of the graduate is not even hinted at. At the end of the (XIX) century, the first papers decorated with vignettes allusive of the city life and inclusive of the graduate’s portrait make their first appearance, at this point still with no satiric connotation. Step by step, by the end of the 1920s and at the beginning of the 1930s, the central figure of the graduate starts to be accompanied by other sketches, more or less related to the character or to episodes of his life, but still with a sober and never vulgar taste. During World War II this habit is obviously put aside and almost disappeared; it came back roaring in the After-War years with much more exuberance.

During the Fifties, the golden age of the goliardic as a genre, quite a lot of papyruses are produced. Techniques change and update thanks to the appearance of new technologies but the basic physiognomy of the papyrus remained the same up to this day. In the last ten or fifteen years a major emphasis was gradually given to the sexual aspects of the graduate’s life (regardless of gender) that are described in the vignettes, with constant and frequently very explicit references to their genitals, almost always represented in the drawings. It must be pointed out that the tradition of the papyrus has spread so as to become a universal practice, even if it is well-rooted especially in the north-east area of our Country, where it has been ritualized to the point of involving a great number of students, even those who do not stand out for their humor. It is such a widespread tradition that the public authority of many cities with big universities have offered specific zones so the papyruses can be hung freely.

In Portogruaro they can usually be found in via Martiri, even though they are lately going through a rough path there because of a public guards’ excessive sense of duty or because of worried entrepreneurs who, in order to preserve general decency or to protect the innocents’ eyes from improper images, remove the papyruses without much thought.

Those who benefit the most of this attitude are doubtlessly the graduates who skip public derision, even though it means that their academic achievement goes by unnoticed.

But what is a little public derision if compared to a centuries-old tradition like that of the papyrus? Especially now that the university has consolidated itself thanks to the introduction of new courses, such a tradition deserves attention.

But do not think that the papyrus responds only to the desire of ridicule… pardon, publicly exhibiting the heroic actions of the graduates and of what friends think of them: it is not so! It is a matter of tradition and traditions must be respected. It is for this reason that in this era of flaming diatribes on the liberty of expression I proudly say: the freedom to the papyrus!

Stefano Zadro

Translation: Elisa Gasparotto