Looking into the Faces of Veterans

"2012 Independent Publishing Award: Outstanding Book of the Year,

Gold Medal, Freedom Fighters). "

For more information please visit: www.portraitsofservice.com

Do you know a special veteran that should be included in this book? If so please contact me directly at: rob@portraitsofservice.com

Aims and Scope

The aim of Portraits of Service - 2012 is to photograph a selection of veterans living in the United States and Europe and elsewhere who have served in a war, regardless of their physical condition.

Robert H. Miller and Andrew Wakeford, both award-winning photographers, are combining their efforts to realize this project. They will work independently and together on both continents to capture compelling photographs of each participating veteran. We are targeting 100 veterans for this project, and we are hoping for a diverse group with greatly differing experiences and situations.

Funded by a grant from the Patton Foundation, the images will be assembled into a traveling exhibit and published as a book of photographs by Patton Publishing in second quarter 2012.

The purpose of the book and traveling exhibit is to focus public attention on living veterans of all wars who have made personal sacrifices and experienced the horrors of war. Upon returning home, many of these vets were met with indifference; worse, many did not receive continuing support or help from their communities. In nearly all cases, it became a struggle to rebuild their lives and restore a sense of normalcy.

About this Book and Exhibition

We, as photographers, are driven to use our professional skills to communicate emotion and perhaps a message. We will be attempting to understand the obstacles each veteran has faced and to recognize their efforts by letting them express it in the form of a picture. Five main topics will be highlighted in our book.

The end result will be a powerful collection of images. These photos will send a message to those who view the book and exhibit that veterans and their families share universal fears and emotions. The key difference between veterans and everyone else is that many are suffering in silence after having made great sacrifices on behalf of the rest of us to ensure our continuing freedom.

The aim of Portraits of Service - 2012 is to photograph a selection of veterans living in the United States and Europe and elsewhere who have served in a war, regardless of their physical condition.

Robert H. Miller and Andrew Wakeford, both award-winning photographers, are combining their efforts to realize this project. They will work independently and together on both continents to capture compelling photographs of each participating veteran. We are targeting 100 veterans for this project, and we are hoping for a diverse group with greatly differing experiences and situations.

Funded by a grant from the Patton Foundation, the images will be assembled into a traveling exhibit and published as a book of photographs by Patton Publishing in second quarter 2012.

The purpose of the book and traveling exhibit is to focus public attention on living veterans of all wars who have made personal sacrifices and experienced the horrors of war. Upon returning home, many of these vets were met with indifference; worse, many did not receive continuing support or help from their communities. In nearly all cases, it became a struggle to rebuild their lives and restore a sense of normalcy.

About this Book and Exhibition

We, as photographers, are driven to use our professional skills to communicate emotion and perhaps a message. We will be attempting to understand the obstacles each veteran has faced and to recognize their efforts by letting them express it in the form of a picture. Five main topics will be highlighted in our book.

The end result will be a powerful collection of images. These photos will send a message to those who view the book and exhibit that veterans and their families share universal fears and emotions. The key difference between veterans and everyone else is that many are suffering in silence after having made great sacrifices on behalf of the rest of us to ensure our continuing freedom.

Jessica Goodell

She helped to retrieve, identify, and process fallen marines

Deployment: Iraq

Served: U.S. Marines, Mortuary Affairs Unit

Nationality: American

Residence: Buffalo, New York

Occupation: Author, graduate student

“Sometimes we had to scoop up the remains with our hands or retrieve limbs and place it all into a body bag.”

Jessica Goodell, twenty-eight, is soft spoken and eloquent. Her Iraq War experience is almost impossiblefor anyone to fully comprehend. Her beautiful eyes become dull and lifeless themoment she begins to tell her story of serving in the Mortuary Affairs Unit ofthe United States Marines.

“It was our job to do the work of retrieving the remains of fallen Marines. We were also responsiblefor identifying the bodies and preparing them to be sent home to their families,” she explains. “I was involved with this work for nine months, from February to November 2004.”

Goodell wore a hazmatsuit when she was called to a scene where Marines were reported down. Her jobwas typically unpredictable, dangerous, and horrific. “We were prepared foralmost anything,” she recalls. In Iraq soldiers often died as the result of anexplosion, and in most cases, says Goodell, they would not find a clean body onthe ground.

“Sometimes it is alittle more messy,” she says. The hazmat suit protected her from the effects ofexploded bodies that were no longer intact. “Sometimes we had to scoop up there remains with our hands or retrieve limbs and place it all into a body bag,” she recalls. “It is so important to collect everything, as much as possible, so that the family can know that they have all of their loved one’s remains.”

Goodell explains that there is a distinct difference between the feel of body bags containing intact bodies and the ones that contain shattered remains: “The shattered remains just slide together in the center of the bag when it is lifted.” She also remembersthe stench of death: “For nine months it was on everything we owned. It permeated our skin and became the permanent smell inside our noses. It also caused us to not want to eat. We all struggled with eating. It was incrediblyhard.”

Goodell recalls this sad experience from the early days of her deployment with Mortuary Affairs:

We had a call that a marine was down andsome of the soldiers would be bringing him to us for processing. When the body arrived it was whole and pretty much intact. My aide was busy getting the hands on the top of the body in preparation for fingerprinting. Suddenly, he said,‘Goodell, you might want to look at this.’ When I looked, the arms were moving very fluidly and easily. Normally this is not the case. I looked at themarine’s chest, and I watched it slowly rise and fall. Alarmed, we immediately notified our Sir [officer]. He came over and saw what we were experiencing and quickly summoned the doctor on duty. He came over to our station and examined the body. After a long, uneasy pause, he said, ‘there is nothing we can do right now for this marine. We just have to wait.’ I imagine now that it must have been a situation where nothing could have been done. But at the time, I just couldn’t imagine waiting. I said quietly to myself over and over again: ‘Wait for what? Wait for what?’

The marine slowly died,and they proceeded with processing his remains.

Today Goodell is a graduate student studying to become a clinical psychotherapist specializing in trauma, with a focus on veterans. Her book Shade It Black: Death and After in Iraq is about her nine months with the Mortuary Affairs Unit.

Photo Robert H. Miller

She helped to retrieve, identify, and process fallen marines

Deployment: Iraq

Served: U.S. Marines, Mortuary Affairs Unit

Nationality: American

Residence: Buffalo, New York

Occupation: Author, graduate student

“Sometimes we had to scoop up the remains with our hands or retrieve limbs and place it all into a body bag.”

Jessica Goodell, twenty-eight, is soft spoken and eloquent. Her Iraq War experience is almost impossiblefor anyone to fully comprehend. Her beautiful eyes become dull and lifeless themoment she begins to tell her story of serving in the Mortuary Affairs Unit ofthe United States Marines.

“It was our job to do the work of retrieving the remains of fallen Marines. We were also responsiblefor identifying the bodies and preparing them to be sent home to their families,” she explains. “I was involved with this work for nine months, from February to November 2004.”

Goodell wore a hazmatsuit when she was called to a scene where Marines were reported down. Her jobwas typically unpredictable, dangerous, and horrific. “We were prepared foralmost anything,” she recalls. In Iraq soldiers often died as the result of anexplosion, and in most cases, says Goodell, they would not find a clean body onthe ground.

“Sometimes it is alittle more messy,” she says. The hazmat suit protected her from the effects ofexploded bodies that were no longer intact. “Sometimes we had to scoop up there remains with our hands or retrieve limbs and place it all into a body bag,” she recalls. “It is so important to collect everything, as much as possible, so that the family can know that they have all of their loved one’s remains.”

Goodell explains that there is a distinct difference between the feel of body bags containing intact bodies and the ones that contain shattered remains: “The shattered remains just slide together in the center of the bag when it is lifted.” She also remembersthe stench of death: “For nine months it was on everything we owned. It permeated our skin and became the permanent smell inside our noses. It also caused us to not want to eat. We all struggled with eating. It was incrediblyhard.”

Goodell recalls this sad experience from the early days of her deployment with Mortuary Affairs:

We had a call that a marine was down andsome of the soldiers would be bringing him to us for processing. When the body arrived it was whole and pretty much intact. My aide was busy getting the hands on the top of the body in preparation for fingerprinting. Suddenly, he said,‘Goodell, you might want to look at this.’ When I looked, the arms were moving very fluidly and easily. Normally this is not the case. I looked at themarine’s chest, and I watched it slowly rise and fall. Alarmed, we immediately notified our Sir [officer]. He came over and saw what we were experiencing and quickly summoned the doctor on duty. He came over to our station and examined the body. After a long, uneasy pause, he said, ‘there is nothing we can do right now for this marine. We just have to wait.’ I imagine now that it must have been a situation where nothing could have been done. But at the time, I just couldn’t imagine waiting. I said quietly to myself over and over again: ‘Wait for what? Wait for what?’

The marine slowly died,and they proceeded with processing his remains.

Today Goodell is a graduate student studying to become a clinical psychotherapist specializing in trauma, with a focus on veterans. Her book Shade It Black: Death and After in Iraq is about her nine months with the Mortuary Affairs Unit.

Photo Robert H. Miller

Dante J. Orsini

FranklinDelano Roosevelt’s personal guard

Deployment: World War II

Served: U.S. Marines

Nationality: American

Residence: South Glens Falls, New York

Occupation: Retired executive, Scott Paper Company

“I was with President Roosevelt when he dedicated the JeffersonMemorial and when he placed

the cornerstone for the Bethesda Naval Hospital. Both were very memorablemoments,”

Dressed in a crisp bluesuit and brimming with enthusiasm, Dante Orsini appears far younger than his ninety-one years. His voice is compelling, and he speaks of his World War IIexperiences as if it all happened

only yesterday.

Because there were no jobs to be found in 1939, Orsini and a close friend decided to enlist in the marines. But after enduring grueling boot camp training, the officer in charge called Orsini into his office and informed him that his superior typing skills were needed in Washington, DC. Orsini left for the nation’s capital, his ego slightly deflated, to assume his new duties. “I just could not believe this,” Orsini recalls. “I wanted to go to Europe—not be a typist.” It was two years before the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the crisis in Europe was escalating, recalls Orsini. “Soon I received another call to report to my command officer, and that is when he dropped a bombshell. I found myself assigned to the White House guard staff.” Only nineteen years old, Orsini had become a member of an elite squad that would be guarding the president.

In fact, Orsini wasassigned to become Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s personal guard. In 1941 he stood only a few feet away as President Roosevelt was sworn in for his historic third term. Orsini attended numerous high-profile events and formed a realrelationship with Roosevelt. “I was with President Roosevelt when he dedicated the Jefferson Memorial and when he placed the cornerstone for the BethesdaNaval Hospital. Both were very memorable moments,” says Orsini. “My best experience came when I was on a train guarding the president and we went toWarm Springs, Georgia, for his vacation. He was the most relaxed on that trip—Roosevelt enjoyed life tremendously.”

The lives of Roosevelt,Orsini, and everyone in America changed suddenly and forever on the early morning of December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Soon Orsini was standing off to the side of the president as he delivered his “Dayof Infamy” speech to the world. “I can tell you this,” says Orsini, “I was never so moved with emotion in my entire life. Here was the president tellingthe world that the United States and its allies were going to take care of those bastards who dragged us into the war. “The best part of it allwas that we did. Roosevelt kept his promise to the world.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

FranklinDelano Roosevelt’s personal guard

Deployment: World War II

Served: U.S. Marines

Nationality: American

Residence: South Glens Falls, New York

Occupation: Retired executive, Scott Paper Company

“I was with President Roosevelt when he dedicated the JeffersonMemorial and when he placed

the cornerstone for the Bethesda Naval Hospital. Both were very memorablemoments,”

Dressed in a crisp bluesuit and brimming with enthusiasm, Dante Orsini appears far younger than his ninety-one years. His voice is compelling, and he speaks of his World War IIexperiences as if it all happened

only yesterday.

Because there were no jobs to be found in 1939, Orsini and a close friend decided to enlist in the marines. But after enduring grueling boot camp training, the officer in charge called Orsini into his office and informed him that his superior typing skills were needed in Washington, DC. Orsini left for the nation’s capital, his ego slightly deflated, to assume his new duties. “I just could not believe this,” Orsini recalls. “I wanted to go to Europe—not be a typist.” It was two years before the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the crisis in Europe was escalating, recalls Orsini. “Soon I received another call to report to my command officer, and that is when he dropped a bombshell. I found myself assigned to the White House guard staff.” Only nineteen years old, Orsini had become a member of an elite squad that would be guarding the president.

In fact, Orsini wasassigned to become Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s personal guard. In 1941 he stood only a few feet away as President Roosevelt was sworn in for his historic third term. Orsini attended numerous high-profile events and formed a realrelationship with Roosevelt. “I was with President Roosevelt when he dedicated the Jefferson Memorial and when he placed the cornerstone for the BethesdaNaval Hospital. Both were very memorable moments,” says Orsini. “My best experience came when I was on a train guarding the president and we went toWarm Springs, Georgia, for his vacation. He was the most relaxed on that trip—Roosevelt enjoyed life tremendously.”

The lives of Roosevelt,Orsini, and everyone in America changed suddenly and forever on the early morning of December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Soon Orsini was standing off to the side of the president as he delivered his “Dayof Infamy” speech to the world. “I can tell you this,” says Orsini, “I was never so moved with emotion in my entire life. Here was the president tellingthe world that the United States and its allies were going to take care of those bastards who dragged us into the war. “The best part of it allwas that we did. Roosevelt kept his promise to the world.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

Brett Felton

Disabled veteran

Deployment: Iraq War

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Warren,Michigan

Occupation: Logistics engineer, General Dynamics Land Systems

“The Iraq War made me numb, almost lifeless.”

Brett Felton, twenty-four, iswearing a Rosary around his neck and a religious bracelet on his left wrist ashe sits in his Warren, Michigan, home talking about his experiences in the Iraq War. Felton stares into space, his eyes wide and almost lifeless, as he describes his fifteen months in hell and explains how he survived an IED attack (improvised explosion device). He paints a surreal picture in pain staking detail. While Felton doesn’t appear disabled, the body under his clothes andthe memories that lodge deep inside his mind tell a completely different story.

“The Iraq War made me numb, almost lifeless.” says Felton. “I arrived in July 2006, and from that day forward my world was filled with the uncertainty of death.” Felton’s eyes tear up as he recalls how much he hated killing people. “But it was either them or me,” he says. “When I came to Iraq I was determined to survive.”

Although Felton wasn’t afraid to die, he says he was anxious most of the time. But the “costs” of war significantly changed his attitude and physical life. Today the Veterans Administration classifies Bret Felton as 70 percent disabled. Felton relives the deadly IED explosion that almost took his life: I was a crow gunner on the very top of a Humvee for route patrol. Insurgents target this first if they plan on an attack. I knew this position was a very dangerous one. My job was surveillance, and I had the gun and the high power scopes with night vision to find them and to take them out if needed. Inside the Humvee were four other soldiers. We relied on each other. It happened when we were nearing the end of an intense fourteen-hour patrol. Some insurgent most likely triggered the IED by a cell phone right when our Humvee was passing over it. We never saw a thing.

Felton saw the explosion before he heard it. It seemed to happen in slow motion. “A thick black cloud of dust and smoke appeared, and inan instant it engulfed us,” he says. “I have never experienced anything likethis−super black and intense. I was choking.”

For a moment the explosion consumed all the surrounding breathable air, with the soldiers taking in dust, smoke, and sand. Soon Felton’s ears were popping, and he could hear an intense painful ringing.“Within seconds I lost all of my hearing,” he recalls. After that he fell unconscious, and when he came to, his first thought was: This is forever. “I thought I was dead,” he says. It took several minutes for Felton to processwhat had happened to him. Realizing he could still hear sounds above the intense ringing in his ears, he became aware of the frantic screaming of his injured squad leader. “Is everyone OK? Is everyone OK?” the squad leader wasshouting. At this moment Felton understood he was not dead and that the pain in his body was escalating.

Occasionally a hint of sunlight glinted through the thick, dark smoke. The Humvee was destroyed, but the men inside had survived−barely. Felton had suffered a closed-head injury, spinal compression,and several other disabling injuries. The others had taken in shrapnel from flying IED and Humvee debris, and all had suffered compression injuries and blunt-force trauma. The injuries inflicted on Felton and his fellow soldiers inthat attack endure today and have changed their lives forever.

“It’s not always the shrapnel that kills the soldier, butthe percussion from the blast,” says Felton. “We were just damn lucky.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

Disabled veteran

Deployment: Iraq War

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Warren,Michigan

Occupation: Logistics engineer, General Dynamics Land Systems

“The Iraq War made me numb, almost lifeless.”

Brett Felton, twenty-four, iswearing a Rosary around his neck and a religious bracelet on his left wrist ashe sits in his Warren, Michigan, home talking about his experiences in the Iraq War. Felton stares into space, his eyes wide and almost lifeless, as he describes his fifteen months in hell and explains how he survived an IED attack (improvised explosion device). He paints a surreal picture in pain staking detail. While Felton doesn’t appear disabled, the body under his clothes andthe memories that lodge deep inside his mind tell a completely different story.

“The Iraq War made me numb, almost lifeless.” says Felton. “I arrived in July 2006, and from that day forward my world was filled with the uncertainty of death.” Felton’s eyes tear up as he recalls how much he hated killing people. “But it was either them or me,” he says. “When I came to Iraq I was determined to survive.”

Although Felton wasn’t afraid to die, he says he was anxious most of the time. But the “costs” of war significantly changed his attitude and physical life. Today the Veterans Administration classifies Bret Felton as 70 percent disabled. Felton relives the deadly IED explosion that almost took his life: I was a crow gunner on the very top of a Humvee for route patrol. Insurgents target this first if they plan on an attack. I knew this position was a very dangerous one. My job was surveillance, and I had the gun and the high power scopes with night vision to find them and to take them out if needed. Inside the Humvee were four other soldiers. We relied on each other. It happened when we were nearing the end of an intense fourteen-hour patrol. Some insurgent most likely triggered the IED by a cell phone right when our Humvee was passing over it. We never saw a thing.

Felton saw the explosion before he heard it. It seemed to happen in slow motion. “A thick black cloud of dust and smoke appeared, and inan instant it engulfed us,” he says. “I have never experienced anything likethis−super black and intense. I was choking.”

For a moment the explosion consumed all the surrounding breathable air, with the soldiers taking in dust, smoke, and sand. Soon Felton’s ears were popping, and he could hear an intense painful ringing.“Within seconds I lost all of my hearing,” he recalls. After that he fell unconscious, and when he came to, his first thought was: This is forever. “I thought I was dead,” he says. It took several minutes for Felton to processwhat had happened to him. Realizing he could still hear sounds above the intense ringing in his ears, he became aware of the frantic screaming of his injured squad leader. “Is everyone OK? Is everyone OK?” the squad leader wasshouting. At this moment Felton understood he was not dead and that the pain in his body was escalating.

Occasionally a hint of sunlight glinted through the thick, dark smoke. The Humvee was destroyed, but the men inside had survived−barely. Felton had suffered a closed-head injury, spinal compression,and several other disabling injuries. The others had taken in shrapnel from flying IED and Humvee debris, and all had suffered compression injuries and blunt-force trauma. The injuries inflicted on Felton and his fellow soldiers inthat attack endure today and have changed their lives forever.

“It’s not always the shrapnel that kills the soldier, butthe percussion from the blast,” says Felton. “We were just damn lucky.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

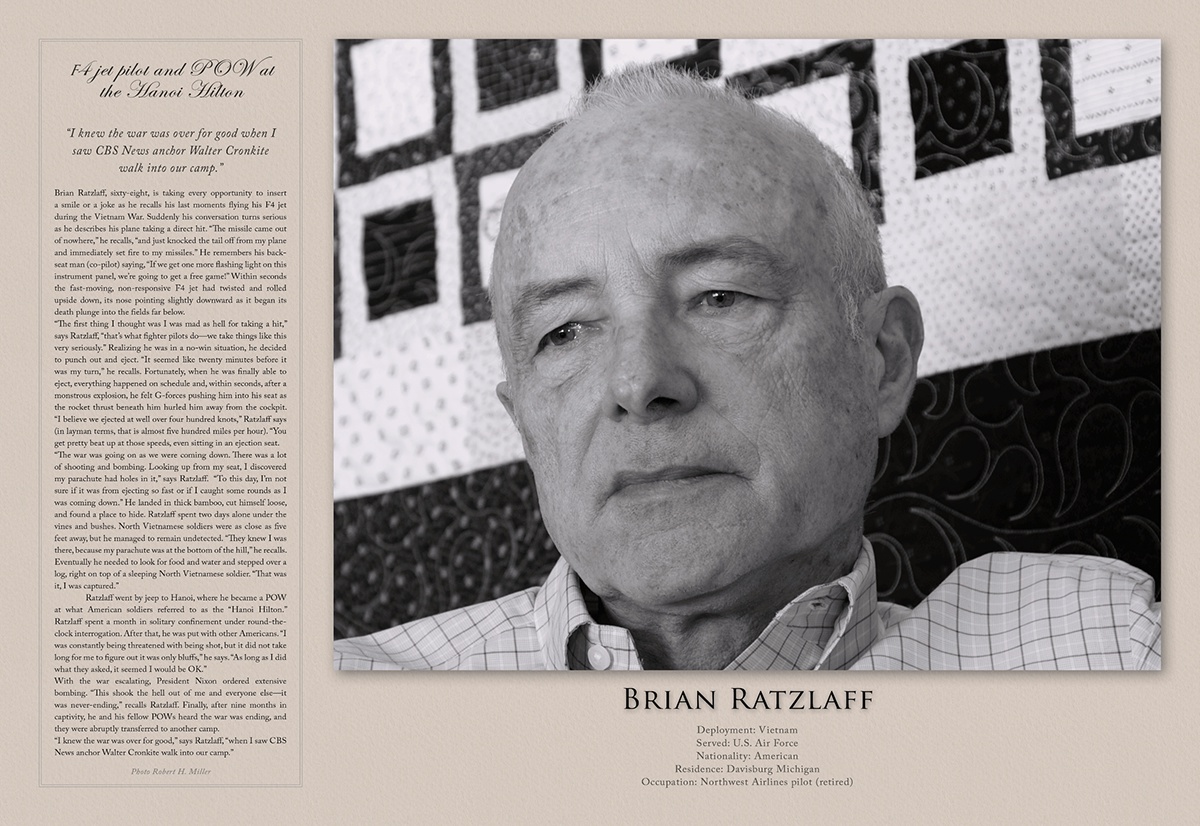

Brian Ratzlaff

F4 jet pilot and POW at the Hanoi Hilton

Deployment: Vietnam

Served: U.S. Air Force

Nationality: American

Residence: Davisburg Michigan

Occupation: Northwest Airlines pilot (retired)

“I knew the war was over for good when I saw CBS News anchor WalterCronkite walk into our camp.”

Brian Ratzlaff ,sixty-eight, is taking every opportunity to insert a smile or a joke as he recalls his last moments flying his F4 jet during the Vietnam War. Suddenly his conversation turns serious as he describes his plane taking a direct hit. “The missile came out of nowhere,” he recalls, “and just knocked the tail off from my plane and immediately set fire to my missiles.” He remembers his back-seatman (co-pilot) saying, “If we get one more flashing light on this instrument panel, we’re going to get a free game!” Within seconds the fast-moving, non-responsiveF4 jet had twisted and rolled upside down, its nose pointing slightly downward as it began its death plunge into the fields far below.

“The first thing I thought was I was mad as hell for taking a hit,” says Ratzlaff, “that’s what fighter pilots do—we take things like this very seriously.” Realizing he was ina no-win situation, he decided to punch out and eject. “It seemed like twenty minutes before it was my turn,” he recalls. Fortunately, when he was finally able to eject, everything happened on schedule and, within seconds, after a monstrous explosion, he felt G-forces pushing him into his seat as the rocket thrust beneath him hurled him away from the cockpit. “I believe we ejected at well over four hundred knots,” Ratzlaff says (in layman terms, that is almost five hundred miles per hour). “You get pretty beat up at those speeds, even sitting in an ejection seat.

“The war was going on as we were coming down. There was a lot of shooting and bombing. Looking up from my seat, I discovered my parachute had holes in it,” says Ratzlaff. “To this day, I’m not sure if it was from ejecting so fast or if I caught some rounds as I was coming down.” He landed in thick bamboo, cut himself loose, and found a place to hide. Ratzlaff spent two days alone under the vines and bushes. North Vietnamese soldiers were as close as five feet away, but he managed to remain undetected. “They knew I was there, because my parachute was at the bottom of the hill,” he recalls. Eventually he needed to look for food and water and stepped over a log, right on top of asleeping North Vietnamese soldier. “That was it, I was captured.”

Ratzlaff went by jeep to Hanoi, where he became a POW at what American soldiers referred to as the “Hanoi Hilton.” Ratzlaff spent a month insolitary confinement under round-the-clock interrogation. After that, he was put with other Americans. “I was constantly being threatened with being shot,but it did not take long for me to figure out it was only bluffs,” he says. “As long as I did what they asked, it seemed I would be OK.”

With the war escalating, President Nixon ordered extensive bombing. “This shook the hell out of me andeveryone else—it was never-ending,” recalls Ratzlaff. Finally, after nine months in captivity, he and his fellow POWs heard the war was ending, and they were abruptly transferred to another camp.

“I knew the war was over for good,” says Ratzlaff, “when I saw CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite walk into our camp.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

F4 jet pilot and POW at the Hanoi Hilton

Deployment: Vietnam

Served: U.S. Air Force

Nationality: American

Residence: Davisburg Michigan

Occupation: Northwest Airlines pilot (retired)

“I knew the war was over for good when I saw CBS News anchor WalterCronkite walk into our camp.”

Brian Ratzlaff ,sixty-eight, is taking every opportunity to insert a smile or a joke as he recalls his last moments flying his F4 jet during the Vietnam War. Suddenly his conversation turns serious as he describes his plane taking a direct hit. “The missile came out of nowhere,” he recalls, “and just knocked the tail off from my plane and immediately set fire to my missiles.” He remembers his back-seatman (co-pilot) saying, “If we get one more flashing light on this instrument panel, we’re going to get a free game!” Within seconds the fast-moving, non-responsiveF4 jet had twisted and rolled upside down, its nose pointing slightly downward as it began its death plunge into the fields far below.

“The first thing I thought was I was mad as hell for taking a hit,” says Ratzlaff, “that’s what fighter pilots do—we take things like this very seriously.” Realizing he was ina no-win situation, he decided to punch out and eject. “It seemed like twenty minutes before it was my turn,” he recalls. Fortunately, when he was finally able to eject, everything happened on schedule and, within seconds, after a monstrous explosion, he felt G-forces pushing him into his seat as the rocket thrust beneath him hurled him away from the cockpit. “I believe we ejected at well over four hundred knots,” Ratzlaff says (in layman terms, that is almost five hundred miles per hour). “You get pretty beat up at those speeds, even sitting in an ejection seat.

“The war was going on as we were coming down. There was a lot of shooting and bombing. Looking up from my seat, I discovered my parachute had holes in it,” says Ratzlaff. “To this day, I’m not sure if it was from ejecting so fast or if I caught some rounds as I was coming down.” He landed in thick bamboo, cut himself loose, and found a place to hide. Ratzlaff spent two days alone under the vines and bushes. North Vietnamese soldiers were as close as five feet away, but he managed to remain undetected. “They knew I was there, because my parachute was at the bottom of the hill,” he recalls. Eventually he needed to look for food and water and stepped over a log, right on top of asleeping North Vietnamese soldier. “That was it, I was captured.”

Ratzlaff went by jeep to Hanoi, where he became a POW at what American soldiers referred to as the “Hanoi Hilton.” Ratzlaff spent a month insolitary confinement under round-the-clock interrogation. After that, he was put with other Americans. “I was constantly being threatened with being shot,but it did not take long for me to figure out it was only bluffs,” he says. “As long as I did what they asked, it seemed I would be OK.”

With the war escalating, President Nixon ordered extensive bombing. “This shook the hell out of me andeveryone else—it was never-ending,” recalls Ratzlaff. Finally, after nine months in captivity, he and his fellow POWs heard the war was ending, and they were abruptly transferred to another camp.

“I knew the war was over for good,” says Ratzlaff, “when I saw CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite walk into our camp.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

Frank Denius

Forward observer, 30th Infantry Division

Deployment: World War II, Europe

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Austin, Texas

Occupation: Attorney (retired)

“On the night of August 6, the German defenses had 70,000 men and fourPanzer divisions ready to assault the 30th Infantry Division in a desperate attempt to seize Mortain.”

Frank Denius is eighty-six but appears much younger. He exudes warmth and caring—Denius is avery nice man. But his smile disappears and his eyes fill with tears when he begins to talk about the horrific Battle of Mortain, which began exactly two months after D-Day, on August 6, 1944. Frank was one of seven hundred men ofthe 30th Infantry Division assigned to hold Hill 314, a mission General Eisenhower had deemed critical.

On the second day of the battle, Denius’s commanding officer had become paralyzed with fear and lay curled up in a ball in a foxhole unable to lead orfight. “He was a mess, shivering and nonresponsive,” recalls Denius. “Somebody needed to take command or else we would die.” Frank immediately began leading the fight against the approaching Germans. He and his fellow soldiers summonedup reservoirs of determination and courage and were able to prevail in the battle for Hill 314, forever changing history. The direction of the war had nowturned in favor of the Americans.

The brutal Battle of Mortain lasted six-and-a-half days, and it nearly wiped out the 30th Infantry, which had held out against all odds. Only three hundred of the seven hundred men who had originally marched up the hill lived to march down off it. Another thirty were captured by the Germans as prisoners of war. The men on Hill 314 became known as the “Lost Battalion.” The Battle of Mortain has been compared by war experts and historians to the Battle of theAlamo.

Photo Robert H. Miller

Forward observer, 30th Infantry Division

Deployment: World War II, Europe

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Austin, Texas

Occupation: Attorney (retired)

“On the night of August 6, the German defenses had 70,000 men and fourPanzer divisions ready to assault the 30th Infantry Division in a desperate attempt to seize Mortain.”

Frank Denius is eighty-six but appears much younger. He exudes warmth and caring—Denius is avery nice man. But his smile disappears and his eyes fill with tears when he begins to talk about the horrific Battle of Mortain, which began exactly two months after D-Day, on August 6, 1944. Frank was one of seven hundred men ofthe 30th Infantry Division assigned to hold Hill 314, a mission General Eisenhower had deemed critical.

On the second day of the battle, Denius’s commanding officer had become paralyzed with fear and lay curled up in a ball in a foxhole unable to lead orfight. “He was a mess, shivering and nonresponsive,” recalls Denius. “Somebody needed to take command or else we would die.” Frank immediately began leading the fight against the approaching Germans. He and his fellow soldiers summonedup reservoirs of determination and courage and were able to prevail in the battle for Hill 314, forever changing history. The direction of the war had nowturned in favor of the Americans.

The brutal Battle of Mortain lasted six-and-a-half days, and it nearly wiped out the 30th Infantry, which had held out against all odds. Only three hundred of the seven hundred men who had originally marched up the hill lived to march down off it. Another thirty were captured by the Germans as prisoners of war. The men on Hill 314 became known as the “Lost Battalion.” The Battle of Mortain has been compared by war experts and historians to the Battle of theAlamo.

Photo Robert H. Miller

Ruth (Heidi) Hyde-Cole

Playinggames with Allied soldiers

Deployment: World War II, England

Served: The Red Cross

Nationality: American

Residence: Queensbury, New York

Occupation: Homemaker, nursery school educator, and professional Girl Scout coordinator(retired)

“There were so many men who desperately needed attention and someone totalk to.”

Heidi Hyde-Cole,ninety-one, wears her original Red Cross pin on the right lapel of her coat. She is very proud of her service with the international humanitarian organization in England during World War II.

Warm, friendly, and witty, Hyde-Cole still exhibits the passion and drive that sustained her when she took on that war assignment sixty-seven years ago.“I wear my pin everyday,” she says, “and I am so glad I had the chance to serve.” Hyde-Cole says her job description back then was simple: “I was to play games with the Allied soldiers.” Games soon turned into discussions. “There were so many men who desperately needed attention and someone to talk to,” she recalls. “Any diversion from that horrible war was a welcome relief for them. Most of the soldiers were scared to death to return to the front lines of fighting.”

Hyde-Cole remembers theplight of one soldier in particular: “This poor man was covered with burns from his head to his toes. He had white bandages wrapped around him, and the only openings were his eyes, mouth and ears.” He still managed to smile, she remembers, but she knew his pain and suffering were intense. “At first this soldier wanted nothing to do with a recreation director,” she says, “because it reminded him too much of home.” But soon, she says, “he warmed up to me and benefited from being diverted from the thoughts of his injuries.”

Hyde-Cole remembers her Red Cross experience as an adventure. She decided to volunteer because she wasn’t married and wanted to do whatever she could to support the war effort.“One of the scariest parts was coming over to England on the Queen Mary,” says Hyde-Cole. “The Germans submarines laid a target on any boat that was crossing the Atlantic.” All the ships were zig-zagging their way across the ocean, she says, and, fortunately, “the Queen Mary was built for speed and needed no escort. I remember falling out of bed late one night on one quick zag. Or was it a zig? We eventually arrived safely in England.” She also remembers an English waiter in the dining room of the ship. “He was an interesting fellow,” says Hyde-Cole.“I finally got up the nerve to ask him if he had a girlfriend. He told me, ‘Oh, no. I have a little bit of fluff in every port.’ ”

For the first time inher life, Heidi Hyde-Cole was speechless.

Photo Robert H. Miller

Playinggames with Allied soldiers

Deployment: World War II, England

Served: The Red Cross

Nationality: American

Residence: Queensbury, New York

Occupation: Homemaker, nursery school educator, and professional Girl Scout coordinator(retired)

“There were so many men who desperately needed attention and someone totalk to.”

Heidi Hyde-Cole,ninety-one, wears her original Red Cross pin on the right lapel of her coat. She is very proud of her service with the international humanitarian organization in England during World War II.

Warm, friendly, and witty, Hyde-Cole still exhibits the passion and drive that sustained her when she took on that war assignment sixty-seven years ago.“I wear my pin everyday,” she says, “and I am so glad I had the chance to serve.” Hyde-Cole says her job description back then was simple: “I was to play games with the Allied soldiers.” Games soon turned into discussions. “There were so many men who desperately needed attention and someone to talk to,” she recalls. “Any diversion from that horrible war was a welcome relief for them. Most of the soldiers were scared to death to return to the front lines of fighting.”

Hyde-Cole remembers theplight of one soldier in particular: “This poor man was covered with burns from his head to his toes. He had white bandages wrapped around him, and the only openings were his eyes, mouth and ears.” He still managed to smile, she remembers, but she knew his pain and suffering were intense. “At first this soldier wanted nothing to do with a recreation director,” she says, “because it reminded him too much of home.” But soon, she says, “he warmed up to me and benefited from being diverted from the thoughts of his injuries.”

Hyde-Cole remembers her Red Cross experience as an adventure. She decided to volunteer because she wasn’t married and wanted to do whatever she could to support the war effort.“One of the scariest parts was coming over to England on the Queen Mary,” says Hyde-Cole. “The Germans submarines laid a target on any boat that was crossing the Atlantic.” All the ships were zig-zagging their way across the ocean, she says, and, fortunately, “the Queen Mary was built for speed and needed no escort. I remember falling out of bed late one night on one quick zag. Or was it a zig? We eventually arrived safely in England.” She also remembers an English waiter in the dining room of the ship. “He was an interesting fellow,” says Hyde-Cole.“I finally got up the nerve to ask him if he had a girlfriend. He told me, ‘Oh, no. I have a little bit of fluff in every port.’ ”

For the first time inher life, Heidi Hyde-Cole was speechless.

Photo Robert H. Miller

Roland Stigulinszky

Writer,cartoonist, satirist

Deployment: World War II, Europe

Served: German Wehrmacht

Nationality: German

Residence: Saarbruecken, Germany

Occupation: Graphic-designer and writer

“At the time, I was an enthusiastic member of the Hitler Youth. Theywere good at making it sound like a noble future was in store. Only later didwe wake up to the truth behind the propaganda.”

In the words ofeighty-five-year-old Roland Stigulinszky:

“Hitler visited the Saarin 1934. I saw him with my uncle, who suggested I offer him my hand. I stretched my little arm toward him, but Hitler only had eyes for an old manholding a top hat, and he stood there clasping his right hand and looking into his eyes. One year later, a man with dark hair was talking to my father in my mother’s kitchen. I overheard the name ‘Hitler’ a couple of times through the door and said, ‘I’m for Hitler, too!’ This upset my father, who sent me packing. I heard my parents arguing afterward, and my mother was telling my father, a Hungarian, to keep out of it—as a foreigner, politics wasn’t his business, she told him.

In 1940 I joined the Hitler Youth Air Command. It was an exciting time and, as a result, I was able to take part in training for the Luftwaffe. My mother was delighted, but my father was horrified. He believed the war would be lost as soon as the Americans joined. My mother saw an international role for me in Tokyo or somewhere of importance. So, my life was interesting and its source of inspiration was always the Fuhrer.

In 1944, when I was allowed to join the Luftwaffe and fly a W 34, I thought it couldn’t get much better. The day after my nineteenth birthday, the Berlin radio announced that Hitler had fallen. After that, we knew it was all over. No one had bothered reading Mein Kampf or Streicher’s Der Sturmer, or we might have known what was coming.”

Photo Andrew Wakeford

Writer,cartoonist, satirist

Deployment: World War II, Europe

Served: German Wehrmacht

Nationality: German

Residence: Saarbruecken, Germany

Occupation: Graphic-designer and writer

“At the time, I was an enthusiastic member of the Hitler Youth. Theywere good at making it sound like a noble future was in store. Only later didwe wake up to the truth behind the propaganda.”

In the words ofeighty-five-year-old Roland Stigulinszky:

“Hitler visited the Saarin 1934. I saw him with my uncle, who suggested I offer him my hand. I stretched my little arm toward him, but Hitler only had eyes for an old manholding a top hat, and he stood there clasping his right hand and looking into his eyes. One year later, a man with dark hair was talking to my father in my mother’s kitchen. I overheard the name ‘Hitler’ a couple of times through the door and said, ‘I’m for Hitler, too!’ This upset my father, who sent me packing. I heard my parents arguing afterward, and my mother was telling my father, a Hungarian, to keep out of it—as a foreigner, politics wasn’t his business, she told him.

In 1940 I joined the Hitler Youth Air Command. It was an exciting time and, as a result, I was able to take part in training for the Luftwaffe. My mother was delighted, but my father was horrified. He believed the war would be lost as soon as the Americans joined. My mother saw an international role for me in Tokyo or somewhere of importance. So, my life was interesting and its source of inspiration was always the Fuhrer.

In 1944, when I was allowed to join the Luftwaffe and fly a W 34, I thought it couldn’t get much better. The day after my nineteenth birthday, the Berlin radio announced that Hitler had fallen. After that, we knew it was all over. No one had bothered reading Mein Kampf or Streicher’s Der Sturmer, or we might have known what was coming.”

Photo Andrew Wakeford

John Ciecko Jr.

Force Recon sniper

Deployment: Vietnam

Served: U.S. Marines

Nationality: Polish-American

Residence: Warren, Michigan

Occupation: Retired veteran benefits coordinator, Purple Heart Association

“I was just damn proud to be able to repay the United States forliberating my parents and me.”

Born in a concentration camp in Attenkirchen, Germany, in 1943, John Ciecko Jr., sixty-eight, spent the first seven years of his life as a prisoner of war. He and his parents were liberated in 1945, moving to the safety of a transition camp for refugees. The family lived at the camp for four years until they were offered freedom and a new life in America. John and his parents settled in Michigan, learned English,and became citizens of the United States.

John expresses deep appreciation and gratitude to the U.S. armed forces and the special soldiers who did so much for his family during their time as POWs. After graduating from high school, Ciecko was offered a football scholarship at the University of Michigan. Instead he chose to join the U.S. Marines, where he served for ten years. During that time, he spent thirty-eight months in Vietnam as a Force Recon sniper. On his final tour of duty Ciecko was hit by enemy shrapnel and severely wounded, resulting in the loss of both his legs above the knees. Ciecko came home, where he was hospitalized for two years until he became fully rehabilitated.

He has spent all his working life with the Purple Heart Association, located in AnnArbor, Michigan. Ciecko has successfully helped more than 1,700 veterans securefull post-war benefits.

Photo Robert H. Miller

Force Recon sniper

Deployment: Vietnam

Served: U.S. Marines

Nationality: Polish-American

Residence: Warren, Michigan

Occupation: Retired veteran benefits coordinator, Purple Heart Association

“I was just damn proud to be able to repay the United States forliberating my parents and me.”

Born in a concentration camp in Attenkirchen, Germany, in 1943, John Ciecko Jr., sixty-eight, spent the first seven years of his life as a prisoner of war. He and his parents were liberated in 1945, moving to the safety of a transition camp for refugees. The family lived at the camp for four years until they were offered freedom and a new life in America. John and his parents settled in Michigan, learned English,and became citizens of the United States.

John expresses deep appreciation and gratitude to the U.S. armed forces and the special soldiers who did so much for his family during their time as POWs. After graduating from high school, Ciecko was offered a football scholarship at the University of Michigan. Instead he chose to join the U.S. Marines, where he served for ten years. During that time, he spent thirty-eight months in Vietnam as a Force Recon sniper. On his final tour of duty Ciecko was hit by enemy shrapnel and severely wounded, resulting in the loss of both his legs above the knees. Ciecko came home, where he was hospitalized for two years until he became fully rehabilitated.

He has spent all his working life with the Purple Heart Association, located in AnnArbor, Michigan. Ciecko has successfully helped more than 1,700 veterans securefull post-war benefits.

Photo Robert H. Miller

Frank Towers

Atrocities of war

Deployment: WorldWar II, Europe

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Brooker,Florida

Occupation: Farmer,specializing in the chicken business (retired)

“I often wonder what this world would be like if thosesix million had never perished.”

In early April 1945, the 30th Infantry Division liberated Brunswick and was headed to Magdeburg. “We found something else they weren’t prepared for,” Frank Towers, ninety-four, recalls. It was an idling train crammed with about 2,500 Jews. The cars, which were meant to hold about forty people, each held as many as one hundred. They were so crowded, he said, that it was impossible for everyone to get to the sole bucket in the corner, which was the bathroom. “There was a horrendous stench,” says Towers.“It was so bad our own American boys had to turn around and vomit.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

Atrocities of war

Deployment: WorldWar II, Europe

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Brooker,Florida

Occupation: Farmer,specializing in the chicken business (retired)

“I often wonder what this world would be like if thosesix million had never perished.”

In early April 1945, the 30th Infantry Division liberated Brunswick and was headed to Magdeburg. “We found something else they weren’t prepared for,” Frank Towers, ninety-four, recalls. It was an idling train crammed with about 2,500 Jews. The cars, which were meant to hold about forty people, each held as many as one hundred. They were so crowded, he said, that it was impossible for everyone to get to the sole bucket in the corner, which was the bathroom. “There was a horrendous stench,” says Towers.“It was so bad our own American boys had to turn around and vomit.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

Frank W. Towers Jr.

Sadly, the VietnamWar was not a popular one

Deployment: Vietnam

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Newberry,Florida

Occupation: RetiredFederal Mogul sales executive

“War leads to bonds of friendship unlike any other bonds you will ever create.

After being in the Vietnam jungle for ninety days straight, those bonds become part of your DNA.”

Frank Towers Jr. is stoic and proud. Fit and trim, the sixty-one-year-old appears far younger than his age.Towers recalls the emotions and fears he experienced during the Vietnam War andthe deaths he witnessed there as if they happened yesterday.

Remembering his war, Towers turns serious and begins to speak with candor. “The most vivid and hardest memory for me is of when I left the states for Vietnam,” he says. “For me it was pretty emotional and scary.” He continues: I had no idea what to expect, I didn’t understand the war nor could I grasp the overwhelming feeling of uncertainly that war brings. Everything in my life was turned upside down. Adding to this, the Vietnam culture was so incredibly different—it was a total culture shock for me. When we landed, I was immediately placed in an infantry unit and we all moved into the belly of the jungle to fight for ninety days. Spending three months in a jungle is a miserable experience. While I was out there I contracted malaria and became violently sick after drinking stagnant water out of a bomb crater in order to survive. I finally recovered, but this took a huge toll on my body. As the war proceeded, fighting was almost constant. I was hit by shrapnel but recovered pretty quickly. I lost several of my very best buddies out there, and that forever changed me. I missed those guys, but life in the jungle went on. I did my job and managed to survive and eventually return to the U.S., which was one of the happiest times of my life.

Once Frank Jr. was back from his tour of duty, his father, World War II vet Frank Towers, understood what his son had experienced. “My father was a great support for me,” recalls Towers. “Sadly the Vietnam War was not a popular one, and we were treated very differently than the veterans returning home from World War II.” According to Towers, it was hard to be a veteran back from Vietnam living in the United States at that time. “Nobody cared—nobody asked what it was like to serve or to be over there,” he says. “Some people actually went out of their way to mistreat you. It was really a sad time in America.”

Towers and his father share the experience of serving ina war. Both men received Purple Hearts for injuries they sustained while fighting. But Towers’s father returned to an America that was greeting soldiers with ticker-tape parades and praising them for their service and accomplishments. When Frank Jr. returned to America, he was expected to slip quietly back into society and immediately function normally.

But father and son are equally proud of having servedtheir country in a time of war.

Photo Robert H. Miller

Sadly, the VietnamWar was not a popular one

Deployment: Vietnam

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Newberry,Florida

Occupation: RetiredFederal Mogul sales executive

“War leads to bonds of friendship unlike any other bonds you will ever create.

After being in the Vietnam jungle for ninety days straight, those bonds become part of your DNA.”

Frank Towers Jr. is stoic and proud. Fit and trim, the sixty-one-year-old appears far younger than his age.Towers recalls the emotions and fears he experienced during the Vietnam War andthe deaths he witnessed there as if they happened yesterday.

Remembering his war, Towers turns serious and begins to speak with candor. “The most vivid and hardest memory for me is of when I left the states for Vietnam,” he says. “For me it was pretty emotional and scary.” He continues: I had no idea what to expect, I didn’t understand the war nor could I grasp the overwhelming feeling of uncertainly that war brings. Everything in my life was turned upside down. Adding to this, the Vietnam culture was so incredibly different—it was a total culture shock for me. When we landed, I was immediately placed in an infantry unit and we all moved into the belly of the jungle to fight for ninety days. Spending three months in a jungle is a miserable experience. While I was out there I contracted malaria and became violently sick after drinking stagnant water out of a bomb crater in order to survive. I finally recovered, but this took a huge toll on my body. As the war proceeded, fighting was almost constant. I was hit by shrapnel but recovered pretty quickly. I lost several of my very best buddies out there, and that forever changed me. I missed those guys, but life in the jungle went on. I did my job and managed to survive and eventually return to the U.S., which was one of the happiest times of my life.

Once Frank Jr. was back from his tour of duty, his father, World War II vet Frank Towers, understood what his son had experienced. “My father was a great support for me,” recalls Towers. “Sadly the Vietnam War was not a popular one, and we were treated very differently than the veterans returning home from World War II.” According to Towers, it was hard to be a veteran back from Vietnam living in the United States at that time. “Nobody cared—nobody asked what it was like to serve or to be over there,” he says. “Some people actually went out of their way to mistreat you. It was really a sad time in America.”

Towers and his father share the experience of serving ina war. Both men received Purple Hearts for injuries they sustained while fighting. But Towers’s father returned to an America that was greeting soldiers with ticker-tape parades and praising them for their service and accomplishments. When Frank Jr. returned to America, he was expected to slip quietly back into society and immediately function normally.

But father and son are equally proud of having servedtheir country in a time of war.

Photo Robert H. Miller

Herman Herrera

The hazardsof PTSD combined with too muchmedication and alcohol nearly led to disaster

Deployment:Iraq

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Visalia, Colorado

Occupation: Adventure coordinator, LifeQuest Transitions

“My Humvee was hit during my third deploymentin Iraq. I guess that’s what tipped me over the edge.” Herman Herrera, thirty-two, and a father of two, begins to talk about the time he went over that edge. In February 2008, on a cold and rainy winterday in Baghdad, the Humvee he was riding in was hit by a heat-sensitive bomb.The reality of these bombs had been with Herrera since 2003, when they were still fairly primitive. But over time they became more sophisticated anddeadly, he explains, and during his second deployment in Iraq, in 2006 and 2007, the bombs were a daily factor in his life. The attack on that fateful dayin February 2008 finally took him beyond the breaking point.

Miraculously no one was hurt in the attack, although the back of the Humvee had been blown off. The crew was checked, deemed fit for duty, and sentback in. But for staff sergeant Herrera, that attack signaled for him how wearyhe was of living with frequent explosions, the shock of sudden overwhelming noise, and the terror of anticipating injury or death for himself or his comrades. This was enough for Herrera to go over the edge.

Several months later, in June, Herrera’s unit was called up to aid inthe push into Sadr City. They spent eighteen hours straight in combat every dayfor two weeks, enduring heavy machine-gun and small-arms fire, before being relieved. The temperature was about one hundred degrees outside, and much hotter inside the unit’s Bradley tank. Herrera was horrified by the stress and torment he and his crew suffered as a result of those suffocating hours spent under random fire.

When Herrera returned to the U.S. early in 2009, his wife noticed that his mental health had deteriorated drastically. He was filled with raw anger, and she urged him to seek professional help. His wife made it clear to him that their marriage was on the line, and Herrera sought the help of a therapist. By September 2009 he was taking twelve drugs daily for PTSD, sleep problems,headaches, high blood pressure, anger issues, and bad dreams. His problems qualified him for thirty days of leave.

When he arrived home, his wife advised him to stop taking the dangerous cocktail of medicines. Feeling angry and confused, Herrera wondered why after telling him to get treatment she was now complaining about it. But he decided to take her advice and, without consulting his doctors, he went off his meds cold turkey. He immediately turned to alcohol and began to drink heavily. One night, after his wife and son had gone to bed, Herrera drank until he blacked out; he wokeup in his garage. He heard himself say that he was going to go upstairs to kill his wife. “I didn’t know how to cope with that,” he says. The next day he told his wife what had happened and she became frightened, telling him to go to the hospital.

Herrera ignored her suggestion, and that night he drank alcohol, took sleeping pills, and left suicide notes around. He wrote to his wife that he was sorry and that she deserved better. She later found him alive and stayed with him to keep him from falling asleep.

The next day he agreed to be hospitalized and was admitted to a PTSD clinic away from the pressures of his family life. He eventually left the army and today works out regularly and is employed as an adventure counselor a tLifeQuest Transitions, a nonprofit organization that serves wounded veterans. He believes his worst battles are behind him. Although Herrera still suffers from occasional nightmares, he lives an otherwise normal life.

Photo Andrew Wakeford

The hazardsof PTSD combined with too muchmedication and alcohol nearly led to disaster

Deployment:Iraq

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Visalia, Colorado

Occupation: Adventure coordinator, LifeQuest Transitions

“My Humvee was hit during my third deploymentin Iraq. I guess that’s what tipped me over the edge.” Herman Herrera, thirty-two, and a father of two, begins to talk about the time he went over that edge. In February 2008, on a cold and rainy winterday in Baghdad, the Humvee he was riding in was hit by a heat-sensitive bomb.The reality of these bombs had been with Herrera since 2003, when they were still fairly primitive. But over time they became more sophisticated anddeadly, he explains, and during his second deployment in Iraq, in 2006 and 2007, the bombs were a daily factor in his life. The attack on that fateful dayin February 2008 finally took him beyond the breaking point.

Miraculously no one was hurt in the attack, although the back of the Humvee had been blown off. The crew was checked, deemed fit for duty, and sentback in. But for staff sergeant Herrera, that attack signaled for him how wearyhe was of living with frequent explosions, the shock of sudden overwhelming noise, and the terror of anticipating injury or death for himself or his comrades. This was enough for Herrera to go over the edge.

Several months later, in June, Herrera’s unit was called up to aid inthe push into Sadr City. They spent eighteen hours straight in combat every dayfor two weeks, enduring heavy machine-gun and small-arms fire, before being relieved. The temperature was about one hundred degrees outside, and much hotter inside the unit’s Bradley tank. Herrera was horrified by the stress and torment he and his crew suffered as a result of those suffocating hours spent under random fire.

When Herrera returned to the U.S. early in 2009, his wife noticed that his mental health had deteriorated drastically. He was filled with raw anger, and she urged him to seek professional help. His wife made it clear to him that their marriage was on the line, and Herrera sought the help of a therapist. By September 2009 he was taking twelve drugs daily for PTSD, sleep problems,headaches, high blood pressure, anger issues, and bad dreams. His problems qualified him for thirty days of leave.

When he arrived home, his wife advised him to stop taking the dangerous cocktail of medicines. Feeling angry and confused, Herrera wondered why after telling him to get treatment she was now complaining about it. But he decided to take her advice and, without consulting his doctors, he went off his meds cold turkey. He immediately turned to alcohol and began to drink heavily. One night, after his wife and son had gone to bed, Herrera drank until he blacked out; he wokeup in his garage. He heard himself say that he was going to go upstairs to kill his wife. “I didn’t know how to cope with that,” he says. The next day he told his wife what had happened and she became frightened, telling him to go to the hospital.

Herrera ignored her suggestion, and that night he drank alcohol, took sleeping pills, and left suicide notes around. He wrote to his wife that he was sorry and that she deserved better. She later found him alive and stayed with him to keep him from falling asleep.

The next day he agreed to be hospitalized and was admitted to a PTSD clinic away from the pressures of his family life. He eventually left the army and today works out regularly and is employed as an adventure counselor a tLifeQuest Transitions, a nonprofit organization that serves wounded veterans. He believes his worst battles are behind him. Although Herrera still suffers from occasional nightmares, he lives an otherwise normal life.

Photo Andrew Wakeford

Buster Simmons

The youngest first sergeant in the entire Army in 1944

Deployment:World War II, Europe

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Farmington, Arkansas

Occupation: Retired sales executive for a trucking firm

“There is no actor who can capture the distress of a dying young manrepeatedly

calling for his mother, knowing he will never return home to see her again.”

At eighty-nine Buster Simmons is quick and witty. But Simmons is hiding many dark memories inside that he would prefer to forget. Confined to a wheel chair after recent hip surgery, Simmons has recovered enough to share a story about his war.

“I was in the Thirtieth Infantry Division and at nineteen was promoted to first sergeant in the medical attachment,” says Simmons. “I was the youngest first sergeant in the entire United States Army in 1942.” Simmons continues: At the Battle of Mortain I had my first real emotional test as a medic. I remember him so clearly. His name was Pettigrew—Billy Pettigrew. During this intense battle in August 1944, Pettigrew was wounded in the neck and upperchest, right near the collarbone, by flying shrapnel. As the shrapnel entered his body it bounced around inside of him causing massive internal damage. When we were finally able to reach him, Pettigrew knew he was dying. We knew, too—it was a gut-wrenching moment.

Simmons pauses, fights back tears, and carefully picks his words.“There is no actor who can capture the horrible distress of a dying young man repeatedly calling for his mother, knowing he will never return home to see heragain.”

Pettigrew eventually slippedaway on Hill 314, despite the care and compassion he had received from Simmons.“Ironically, Pettigrew was a big, solidly-built man,” recalls Simmons. “This made his crying pleas for his mother even harder to hear. I was never in my life so moved with pity—it still wrenches my heart with sorrow even aftersixty-seven years.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

The youngest first sergeant in the entire Army in 1944

Deployment:World War II, Europe

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Farmington, Arkansas

Occupation: Retired sales executive for a trucking firm

“There is no actor who can capture the distress of a dying young manrepeatedly

calling for his mother, knowing he will never return home to see her again.”

At eighty-nine Buster Simmons is quick and witty. But Simmons is hiding many dark memories inside that he would prefer to forget. Confined to a wheel chair after recent hip surgery, Simmons has recovered enough to share a story about his war.

“I was in the Thirtieth Infantry Division and at nineteen was promoted to first sergeant in the medical attachment,” says Simmons. “I was the youngest first sergeant in the entire United States Army in 1942.” Simmons continues: At the Battle of Mortain I had my first real emotional test as a medic. I remember him so clearly. His name was Pettigrew—Billy Pettigrew. During this intense battle in August 1944, Pettigrew was wounded in the neck and upperchest, right near the collarbone, by flying shrapnel. As the shrapnel entered his body it bounced around inside of him causing massive internal damage. When we were finally able to reach him, Pettigrew knew he was dying. We knew, too—it was a gut-wrenching moment.

Simmons pauses, fights back tears, and carefully picks his words.“There is no actor who can capture the horrible distress of a dying young man repeatedly calling for his mother, knowing he will never return home to see heragain.”

Pettigrew eventually slippedaway on Hill 314, despite the care and compassion he had received from Simmons.“Ironically, Pettigrew was a big, solidly-built man,” recalls Simmons. “This made his crying pleas for his mother even harder to hear. I was never in my life so moved with pity—it still wrenches my heart with sorrow even aftersixty-seven years.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

Horst Przybilski & Ike Refice

Foesbut friends: an extraordinary example of friendship after World War II

Deployment: World War II, Europe

Served: German Wehrmacht

Nationality: German

Residence: Seftenberg, Germany

Occupation: Coal mining engineer

Deployment: World War II, Europe

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Fleetville, Pennsylvania

Occupation: Photo-journalist

“I owe my life to you for pulling me out of the fire.” —Horst Przybilski

“I owe my life to you for not killing me.” —Ike Refice

It was 5 o’clock in the morning, January 8, 1945, a few weeks into the Battle of the Bulge. In Dahl, Luxembourg, a squad of the 319th Infantry was defending Asterhof Farm on a steep bluff overlooking the German border. Ike Refice (now eighty-seven) and his buddies held a critical flank position, and they withdrew to the farmhouse under “overwhelming artillery, mortar, and rocket fire” (as the Medal of Honor citation for the squad leader of the 319th would read later).

On the German side, Horst Przybilski (now eighty-three) and his comrades charged up the bluff in bitter cold, exhausted and weak from exposure and poor rations. First they were in the barn, and then they advanced on the house. The battle raged for four hours. As the casualties mounted on both sides, the GIs resorted to throwing live coals from the stove down the steps on the Germans.

Eventually twenty-five Germans surrendered to the decimated American squad. All but two GIs had been wounded, and one was dead. Squad leader Day Turner would earn the Medal of Honor for his actions that day. German soldier Horst Przybilski, seventeen years old and severely wounded in his first day of combat, was on the ground and unconscious with a shattered hip. Refice and Turner carried him out and sent him on to the aid station, where Horst woke up and thought he was in Russia. “I didn’t save Horst’s life,” recalls Refice, “I

did—or we did—what was the right thing to do. If they were bad, I didn’t have to be.”

Przybilski healed up ina POW camp in Fort Devens, Massachusetts, learning English and returning to Germany in 1946. Refice, too, survived the war and returned to Pennsylvania. Over sixty years later, the German soldier came to Asterhof looking for the men who dragged him to safety. Through the efforts of the U.S. Veterans Friends Luxembourg group the two finally met in 2005, and now they get together every June at the group’s Friendship Week. Enemies, friends—only time separates the two.

Photo Andrew Wakeford

Foesbut friends: an extraordinary example of friendship after World War II

Deployment: World War II, Europe

Served: German Wehrmacht

Nationality: German

Residence: Seftenberg, Germany

Occupation: Coal mining engineer

Deployment: World War II, Europe

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Fleetville, Pennsylvania

Occupation: Photo-journalist

“I owe my life to you for pulling me out of the fire.” —Horst Przybilski

“I owe my life to you for not killing me.” —Ike Refice

It was 5 o’clock in the morning, January 8, 1945, a few weeks into the Battle of the Bulge. In Dahl, Luxembourg, a squad of the 319th Infantry was defending Asterhof Farm on a steep bluff overlooking the German border. Ike Refice (now eighty-seven) and his buddies held a critical flank position, and they withdrew to the farmhouse under “overwhelming artillery, mortar, and rocket fire” (as the Medal of Honor citation for the squad leader of the 319th would read later).

On the German side, Horst Przybilski (now eighty-three) and his comrades charged up the bluff in bitter cold, exhausted and weak from exposure and poor rations. First they were in the barn, and then they advanced on the house. The battle raged for four hours. As the casualties mounted on both sides, the GIs resorted to throwing live coals from the stove down the steps on the Germans.

Eventually twenty-five Germans surrendered to the decimated American squad. All but two GIs had been wounded, and one was dead. Squad leader Day Turner would earn the Medal of Honor for his actions that day. German soldier Horst Przybilski, seventeen years old and severely wounded in his first day of combat, was on the ground and unconscious with a shattered hip. Refice and Turner carried him out and sent him on to the aid station, where Horst woke up and thought he was in Russia. “I didn’t save Horst’s life,” recalls Refice, “I

did—or we did—what was the right thing to do. If they were bad, I didn’t have to be.”

Przybilski healed up ina POW camp in Fort Devens, Massachusetts, learning English and returning to Germany in 1946. Refice, too, survived the war and returned to Pennsylvania. Over sixty years later, the German soldier came to Asterhof looking for the men who dragged him to safety. Through the efforts of the U.S. Veterans Friends Luxembourg group the two finally met in 2005, and now they get together every June at the group’s Friendship Week. Enemies, friends—only time separates the two.

Photo Andrew Wakeford

John D. Dingell

U.S. congressman

Deployment: World War II, Europe

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Dearborn, Michigan

Occupation: United States representative,Michigan’s 15th Congressional District

“It was important to me that I receive the same treatment and bear thesame burdens as the other men serving.”

The words of John Dingell:

“In 1944, I entered service in the Army because I wanted to serve my country and was eager to be apart of the war effort. At the time, my father, John D. Dingell Sr., served Michigan’s Sixteenth District in the U.S. House of Representatives. Because it was important to me that I receive the same treatment and bear the same burdens as the other men serving, I always made a point to not mention my father’s career during my time in the Army. I successfully kept it unknown except for one special instance. It was in April 1945, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt died.

FDR had led our nation for more than twelve years. The country was feeling alarmed with a real sense of uncertainty about how to continue as a nation without him during the latter days of World War II. After having looked to FDR for strong leadership for so long and entrusting our country to him tolead us, it was a scary time.

When he died, the vice president, Harry S. Truman, took command of the Armed Forces and began to lead the nation. Around that time, the men inmy unit came to me as I was reading my mail. I looked up, and what seemed like the whole platoon was at the foot of my bunk. They said, ‘Dingell, your dad’s in Congress. Please tell us, who is this new man Truman and what sort of man is he?’ I was surprised that they found out about my dad but told them I’d write to him and ask him. I did just that, and soon after I received a response. I read that letter aloud to the men serving with me and gave them my father’s answer. He wrote that Truman was a great man, he would lead this nation ably, and we could depend on him.

My dad was right on. Harry Truman went on to become not just a great president and amazing visionary but a worthy successor to the mantle of leadership FDR had left him. Harry was a man who made tough decisions, not because they were easy but because they were right. From the White House to the front lines, World War II brought out the best in this nation and its people. I am extremely proud of the small role I played in that effort, and I am grateful and humbled for having been part of such a critical chapter in America’s history.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

U.S. congressman

Deployment: World War II, Europe

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Dearborn, Michigan

Occupation: United States representative,Michigan’s 15th Congressional District

“It was important to me that I receive the same treatment and bear thesame burdens as the other men serving.”

The words of John Dingell:

“In 1944, I entered service in the Army because I wanted to serve my country and was eager to be apart of the war effort. At the time, my father, John D. Dingell Sr., served Michigan’s Sixteenth District in the U.S. House of Representatives. Because it was important to me that I receive the same treatment and bear the same burdens as the other men serving, I always made a point to not mention my father’s career during my time in the Army. I successfully kept it unknown except for one special instance. It was in April 1945, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt died.

FDR had led our nation for more than twelve years. The country was feeling alarmed with a real sense of uncertainty about how to continue as a nation without him during the latter days of World War II. After having looked to FDR for strong leadership for so long and entrusting our country to him tolead us, it was a scary time.

When he died, the vice president, Harry S. Truman, took command of the Armed Forces and began to lead the nation. Around that time, the men inmy unit came to me as I was reading my mail. I looked up, and what seemed like the whole platoon was at the foot of my bunk. They said, ‘Dingell, your dad’s in Congress. Please tell us, who is this new man Truman and what sort of man is he?’ I was surprised that they found out about my dad but told them I’d write to him and ask him. I did just that, and soon after I received a response. I read that letter aloud to the men serving with me and gave them my father’s answer. He wrote that Truman was a great man, he would lead this nation ably, and we could depend on him.

My dad was right on. Harry Truman went on to become not just a great president and amazing visionary but a worthy successor to the mantle of leadership FDR had left him. Harry was a man who made tough decisions, not because they were easy but because they were right. From the White House to the front lines, World War II brought out the best in this nation and its people. I am extremely proud of the small role I played in that effort, and I am grateful and humbled for having been part of such a critical chapter in America’s history.”

Photo Robert H. Miller

James Bell

Today he is no longer homeless

Deployment: Vietnam

Served: U.S. Army

Nationality: American

Residence: Detroit, Michigan

Occupation: Employment specialist, John D. Dingell VA Medical Center

“I was known as crazy James in my neighborhood. I lived as if I was inVietnam.”

Trying to escape the streets of Detroit in the 1960s, the military seemed like a good idea for James Bell. “I tried to join the Army at sixteen,” he says. “Finally, when I was seventeen they took me into basic training.” At the time, Bell had no idea of the impact Vietnam was having on our society. But when told he was going to be sent there to fight, his reaction was, “Hey, I didn’t sign up for this.”