The essay is a response to a statement from Jacques Herzog.

No one has yet truly accomplished [that] in contemporary architecture. Architecture which looks familiar, which does not urge you to look at it, which is quite normal – but at the same time it has also another dimension, a dimension of the new, of something unexpected, something questioning, even disturbing.

Jacques Herzog talking in an extract from ‘Conversation with Jacques Herzog’, with Jeffrey Kipnis, 1997

The idea of subversive art grew out of surrealism. Surrealism dates back to the 1920s, based on philosophical thought and often plays with Freudian, psychoanalytical ideas, with unexpected combinations and non sequiturs. Subversive art is slightly less abstract than surrealism, perhaps more subtler in making the viewer question the artwork.

Adbusters, started in the late 1990s, parodied the world of advertisement and exemplifies the idea of subversion in art. Adbusters take images that are overly saturated in our minds, through repeated bombardment from media, then manipulate them and re-strapline them so as to create an effect that that leads us at first to see a familiar image, but then we realise that we are actually viewing a changed message from consumerist temptation to an overt attack on the capitalistic companies that produce product which are often superfluous to our needs or bad for our health.

Adbusters, 1999, parady of drinking Absolut Vodka

Adbusters approach to parodying media is exactly what Herzog in his statement wants to achieve in architecture. Of course, in architecture it is far more difficult to do this; particularly to produce work that is consciously desired to be ‘disturbing’ in a building. To an extent I think that Herzog statement needs to be questioned. Why would anyone what to make buildings that are deliberately disturbing? Buildings have a different function to the arts. In art people often like to be disturbed, but then to look away. If I am disturbed by reading Bret Easton Ellis I can put the book down. Similarly if I find a painting disturbing I can move on in the art gallery.

Portrait of Myra Hindley, by Marcus Harvey, 1995.

The painting the notorious child murderer was executed by the use of children’s hands to apply the paint to the canvas in the style of monochrome pointillism.

Buildings have a purpose to enhance the quality of life, not to psychologically disrupt it, as Herzog’s statement implies. You cannot escape having to use buildings; our lives are often dictated by being forced to engage with architecture. We have little choice when taking a job about where we are going to spend our working hours and what architectural edifice that will be in. We therefore have a mandatory relationship with buildings. In some cases we cannot detach ourselves from architecture even if we don’t like it; with art, viewers can disengage whenever they chose. Why Herzog wants to make disturbing buildings is unclear. Perhaps it is just a glib end of a statement design to sound sensationalist and maybe trendy?

In film buildings often take a sinister role, like the dystopian urban cityscape in Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Christopher Nolan’s Gotham city. Scott drew inspiration for Blade Runner from Hong Kong.

Cityscape from Blade Runner, Ridley Scott, 1982

Sadly there are countless examples of disturbing architecture and urbanism. Part of the wonder of Hong Kong is its slightly dystopian atmosphere; the word dystopian holds connotations of disturbance. My appreciation of dystopianism in HK might due to my transitory time in HK; if I was condemned to live there, in the looming tenements of Kowloon, would my wonderment evaporate to be replaced by oppression?

A light well in the Chungking Mansions, Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong. Photo taken by author.

The cheek by jowl compression of living in HK. Chungking Mansions, Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong. Photo taken by author.

The disturbing architecture of Hong Kong and many other cities is often born out of economic necessity, high population and laced building regulations; disturbing architecture is almost never done wilfully. Perhaps in the realm of interiors sado-masochistic chambers are the best ensamples of purposely designed spaces to invoke a sense of disturbing, relished by the user.

The idea of idolising disturbance in architecture has a long history. Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720, 1778) exploited the idea in his drawings of prisons which have a quality of early surrealism; the oubliette has a much longer and more disturbing connotation. Piranesi’s drawings in the Carceri series comprised phantasmagoric prison depictions which never existed as built architecture.

Carceri Plate VII - The Drawbridge, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, circa 1745

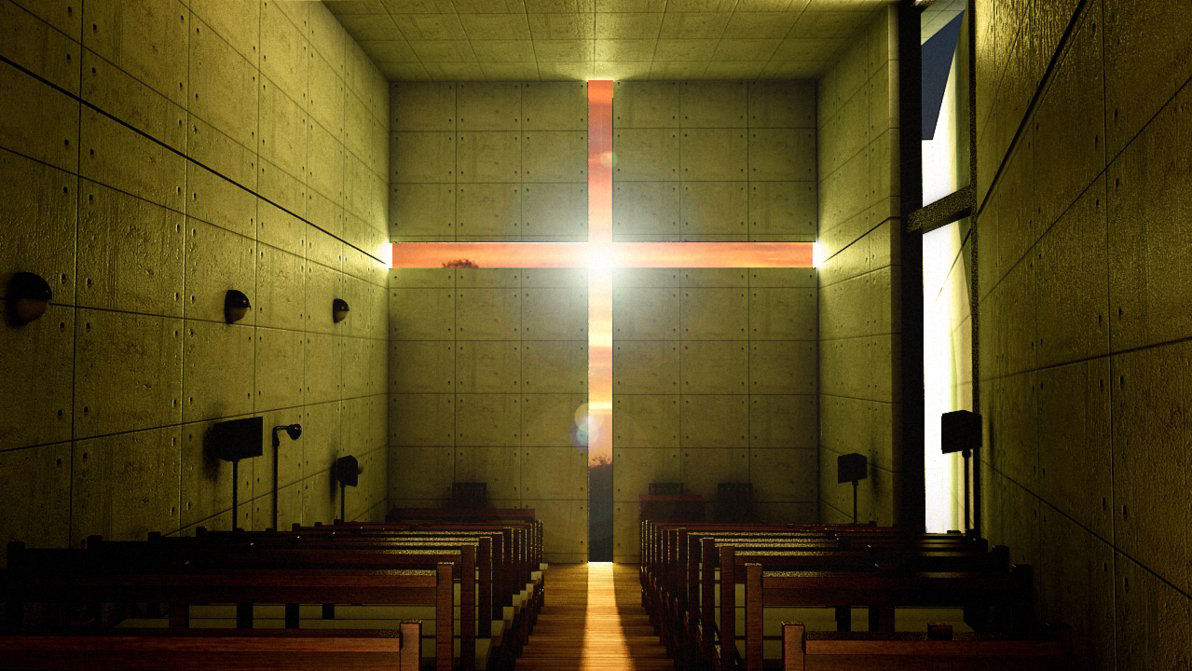

Tadao Ando’s Church of Light, Osaka, Japan, is grounded on millennia of Christian architectural ideas and thoughts. Ando’s use of a contemporary architectural repertoire results in a building that reflects architecture of the present is layered onto a traceable palimpsest of tradition. One feature of the interior is its profound emptiness. Many who enter the church say they find it disturbing. The distinct void and absolute quiet amounts to a sense of serenity. For Ando the idea of 'emptiness' means something different from what is meant by Europeans. It is meant to transfer you into the realm of the spiritual. The emptiness is meant to invade the occupant so there is room for the 'spiritual' to fill them. In The Church of Light the concept of disturbance has been interpreted by some, though for Ando this has a different dimension and is a mechanism, perhaps, to gain a finer relationship with God.

Tadao Ando’s Church of Light, Osaka, Japan, 1989

The word ‘disturbing’ in Hergzog’s statement contradicts what he said previously. He has a desire to explore the traditional in a new context. 'which looks familiar, which does not urge you to look at it, which is quite normal - but at the same time it has another dimension'

Frank Lloyd Wright’s early work, the Prairie Style Home (1893-1914) and the Arts and Crafts movement in general can be seen as a shift from the traditional to modern. What Wright was designing at the turn of the twentieth century corresponds with everything that Hergzog said in his statement, bar being disturbing.

The Robie House, Frank Lloyd Wright, 1910, University of Chicago

Roman Baths, like the Baths of Caracalla in Roam 211-217 AD, with their alternating sizes of bathing room has been referenced by the other Pritzker Prize winning Swiss architect, Peter Zumthor, in the Thermal Baths in Vals. Perhaps Herzog aspires to Zumthor’s precedent of evoking atavistic feelings that Zumthor creates by using leather curtains, petals in pools, special scents. Zumthor’s use of modern materials perhaps relates buildings to future and past simultaneously; concrete mass, bronze handrails, while suggesting mythic qualities by the use of the local vernacular stone.

Thermal Baths Vals, Switzerland, Peter Zumthor, 1996

In the world of interior design, Hergoz’s statement is perhaps more applicable than in architecture. The exterior of the building is often familiar, with the interior taking you into a new dimension that is detached from the structure of the building. Marcel Wanders has produced interiors that transform what we think of as a familiar building into a realm of the new and unexpected by his appropriation of thematic narratives, often producing designs with an unusual twist, based on design methodologies that he acquired from his time with Droog Design.

Hallway of Mondrian South Beach, with references to Cinderella and Lewis Carroll,

Marcel Wanders, Florida, US, 2008

Hergzog calls for ‘Architecture that looks familiar but does not urge you to look at it.’ This is contrary to many of the ideas in architectural practice today. We live in an age of iconic architectural statements. Architects desire recognition through uniqueness and individuality and to an existent have lost touch with the historic architectural traditions that we in the west have been brought up with. Much of this is to do with the popularisation and promotion of distinctive buildings in the media: if you want to be recognised as an architect you need a unique approach to design that distinguishes you from others. This in part has led to architects abandoning the idea of designing buildings that have a link to a historical traditional, leading to monumental and iconoclastic architecture. Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind and other ‘contemporary architects’ drop architectural sculptures into urban fabrics, with little or no connection to the historical precedent of the urban environment.

David Chipperfield curated the Venice Architectural Biennale this year, themed Common Ground. Chipperfield’s aim was to react to the prevalent professional and cultural tendencies of our time that place such emphasis on individual and isolated actions. In a way Chipperfield was trying to bring a more unified approach to architecture and urbanism, one which looks at integration of postmodern attitudes towards fragmented building juxtaposition within the built environment that are prevalent today. One of the outcomes of this exhibition could be the idea of reinterpretations of traditional buildings with new elements within them intended to blend in with existing urban fabrics.

Norman Foster’s installation at the 2012 Venice Architectural Biennale.

Hergozg’s statement, without the word disturbing, is a call for a reflection of traditional ideas explored in a new context. It is important that the architectural profession does not loss contact with architectural history and tries in new ways to incorporate historical ideas with contemporary practice. It is hard to realise Hergozg objectives from his statement as the architectural profession in general has moved away the ideas of tradition and is focused on the architectural zeitgeist. What Hergozg would like to achieve in his statement is surely possible, for a master like himself, to execute if he is offered the right client and opportunity.

References:

Zumthor P, Peter Zumthor Works - Buildings and projects 1979-1997, Lars Muller Publishers, Baden, 1998

Baek J, Nothingness: Tadao Ando's Christian Sacred Space, Routledge, London, 2009

Dempsey A, Styles, Schools and Movements, Thames & Hudson, London, 2002

Hudson J, Interior Architecture from Brief to Build, Laurence King Publishing, London, 2010